In education, the terms test, measurement, assessment, and evaluation are often used interchangeably, yet they represent distinct concepts with specific purposes and interrelationships. A clear understanding of these terms is fundamental for educators, policymakers, and all stakeholders involved in the process of teaching and learning. This report aims to define these key concepts, explore their applications, and discuss their collective impact on educational practices.

Defining the Concepts

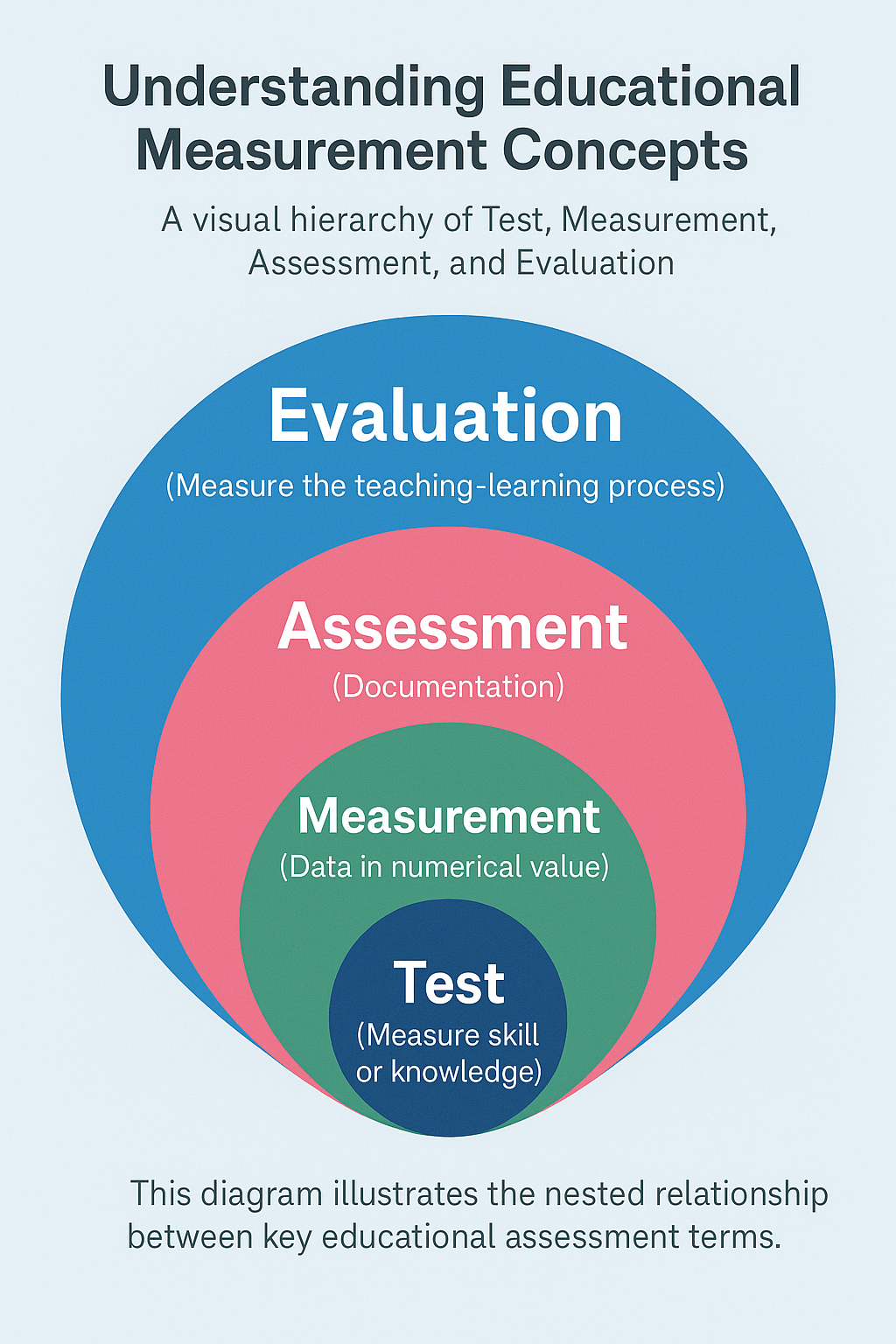

The foundation of effective educational practice lies in accurately understanding how we gather and interpret information about student learning. Test, measurement, assessment, and evaluation are hierarchical concepts that build upon each other to provide a comprehensive view of student progress and program effectiveness.

Test: An Instrument of Observation

A test is a specific tool or instrument used to elicit a sample of behavior or performance from which inferences can be made about a particular trait, knowledge, or skill. Tests are a special form of assessment, typically administered under contrived circumstances to ensure standardization. They can vary widely in format, including objective tests (e.g., multiple-choice, true/false) and subjective tests (e.g., essays, open-ended questions), and can be administered to individuals or groups. Tests can also be standardized, meaning they are administered and scored in a consistent manner, or unstandardized, such as teacher-made tests. The primary purpose of a test is to measure student performance or specific traits.

Measurement: Quantifying Observations

Measurement in education refers to the process of assigning numerical values to attributes or dimensions of an individual’s knowledge, skills, or attitudes. It is the act of collecting data from tests or other assessment tools. While measurement often involves standard instruments like rulers or scales in the physical sciences, in education, it applies to determining things like IQ or quantifying attitudes and preferences. The key output of measurement is quantitative data, typically in the form of scores, which provides information about “what is”. The reliability and usefulness of this information depend on the accuracy of the measuring instruments and the skill with which they are used.

Assessment: Gathering and Interpreting Evidence of Learning

Assessment is a broader term than testing; it is a systematic process of gathering, analyzing, and interpreting evidence to determine how well student learning matches expectations and to refine programs and improve student learning. All tests are assessments, but not all assessments are tests. Assessment encompasses a variety of tools and methods to observe students’ behavior and products, from which reasonable inferences about what students know can be drawn. It is most usefully connected to some known objective or goal for which the assessment is designed.

Assessment can be categorized in several ways:

- Placement, formative, summative, and diagnostic assessment.

- Objective and subjective.

- Referencing (criterion-referenced, norm-referenced, and ipsative).

- Informal and formal.

- Internal and external.

Assessment plays a crucial role in informing teaching, guiding student progress, and checking achievement. It is embedded in the learning process and is closely interconnected with curriculum and instruction.

Evaluation: Making Judgments Based on Evidence

Evaluation is the most complex of these terms and involves making judgments about the worthiness, appropriateness, goodness, or validity of something based on evidence gathered through assessment and measurement. It inherently involves “value”. Evaluation uses the information obtained from assessments to make decisions about programs, policies, and resources, and to judge overall achievement or effectiveness. Teachers constantly evaluate students, usually by comparing intended outcomes (learning, progress, behavior) with what was actually obtained. Evaluation can be process-oriented (examining the methods and procedures) or product-oriented (examining the outcomes).

Interrelationships:

These four concepts are hierarchically related:

- Tests are tools used within the process of assessment.

- Measurement is the quantification of the data obtained from tests and other assessment methods.

- Assessment is the broader process of gathering and interpreting evidence of learning, often using tests and measurements.

- Evaluation uses the information from assessments (which includes data from tests and measurements) to make informed judgments and decisions.

We measure distance, we assess learning, and we evaluate results against a set of criteria. Assessment informs teaching, while evaluation makes judgments about performance and effectiveness.

Assessment of Learning (Summative Assessment)

Assessment of Learning (AoL), often referred to as summative assessment, plays a critical role in the educational landscape. It is primarily designed to certify learning and report on student achievement against established outcomes and standards.

A. Purpose and Objectives of Assessment of Learning

The fundamental purpose of AoL is to evaluate student learning at the end of a defined instructional period—such as a unit, term, semester, or academic year—to determine if students have met grade-level standards or achieved the intended learning outcomes. Its objectives include:

- Certifying Learning and Assigning Grades: AoL is used to make judgments about student performance, often involving assigning grades or ranking students.

- Reporting to Stakeholders: It provides evidence of student achievement to a wide audience, including students themselves, parents, educators, administrators, and policymakers.

- Accountability: Summative assessments ensure accountability within the education system.

- Informing Future Planning: Results from AoL can be used to plan future learning goals and pathways for students and to inform decisions about curriculum changes, instructional strategies, and resource allocation at institutional and systemic levels.

- Evaluating Program Effectiveness: AoL data helps institutions gauge the effectiveness of their educational programs and make necessary improvements.

Core Principles of Effective Assessment of Learning

To be effective, AoL practices must adhere to several core principles:

- Validity: This is the extent to which an assessment accurately measures what it is intended to measure. An assessment must align with curriculum goals and learning objectives. Ensuring test fairness is a fundamental component of establishing validity.

- Reliability: Reliability refers to the consistency and stability of assessment results over time and across different conditions. A reliable assessment yields similar outcomes if administered to the same or a comparable group of students at different times or if scored by different raters. Factors like ambiguous questions or vague marking instructions can affect reliability.

- Fairness: Fairness dictates that all students, irrespective of their background or individual circumstances, have an equal opportunity to demonstrate their learning. Assessments must be free from bias that might disadvantage certain groups and should be culturally inclusive, accommodating diverse learner needs.

- Transparency: This involves clearly communicating the goals, criteria, methods, and expectations of assessments to students and other relevant stakeholders. Students should understand what is being assessed and how their work will be evaluated.

- Authenticity: Authentic assessments mirror real-world situations or tasks, requiring students to apply their learning in practical and meaningful contexts. They often engage higher-order thinking skills.

Methodologies and Implementation of Assessment of Learning

AoL employs various methods, each with specific characteristics:

- Examinations (Exams): Formal, often timed, assessments covering a broad range of content.

- Standardized Tests: Administered and scored consistently to allow for comparisons across large groups (e.g., SAT, ACT, state achievement tests).

- Final Projects: Comprehensive assignments at the end of a course requiring synthesis and application of learned skills.

- Portfolios: Purposeful collections of student work over time demonstrating growth and achievement.

- Criterion-Referenced Assessments: Measure performance against a fixed set of predetermined criteria or learning standards.

- Norm-Referenced Assessments: Compare a student’s performance to that of a normative (average) sample of peers.

Practices in Design, Administration, and Interpretation:

- Design: Assessments must align with learning outcomes and cognitive complexity. Authentic experiences should be incorporated where possible. Workload should be achievable, and instructions and grading criteria (rubrics) must be clear and transparent. Using a variety of methods is also recommended.

- Administration: Consistent conditions and accessibility for all students, including necessary accommodations, are crucial.

- Interpretation: Rubrics should be used for consistent and objective grading. Results should inform future teaching and curriculum decisions, always interpreted within context. Meaningful feedback, even on summative tasks, is important for student development.

Adherence to Professional Standards:

The quality and ethical conduct of AoL, especially high-stakes assessments, are guided by professional standards like those from the American Educational Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association (APA), and National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME). These standards cover validity, reliability/precision, fairness, test design, scoring, and reporting.

D. Theoretical Underpinnings of Assessment of Learning

Different psychological theories influence AoL design:

- Behaviorism: Views learning as an observable change in behavior. Traditional AoL practices like standardized tests with “correct” answers and emphasis on factual recall align with behaviorist principles. Assessment measures observable performance (e.g., test scores) as direct evidence of learning, with reinforcement (grades) playing a key role.

- Cognitivism: Focuses on internal mental processes like memory, problem-solving, and reasoning. This perspective encourages AoL designs that assess deeper understanding and the application, analysis, and evaluation of information.

- Constructivism: Posits that learners actively construct their own knowledge through experience and interaction. This theory favors authentic assessment methods like performance-based tasks and portfolios that allow students to demonstrate constructed understanding in meaningful contexts. While often emphasizing formative assessment, its principles can inform summative tasks requiring application and problem-solving.

Conceptual Frameworks in AoL:

Frameworks like the SOLO (Structure of the Observed Learning Outcome) Taxonomy help design and interpret summative assessments by distinguishing hierarchical levels of understanding (prestructural, unistructural, multistructural, relational, extended abstract) based on cognitive complexity. This allows assessment of the depth of understanding rather than just recall. Bloom’s Taxonomy (Revised) also guides the design of AoL tasks aligned with various levels of cognitive demand (Remembering, Understanding, Applying, Analyzing, Evaluating, Creating).

How Assessment Influences Teaching and Learning

The “washback effect” refers to the impact of testing on curriculum design, teaching practices, and learning behaviors. Teachers may teach directly for specific test preparation, or learners might focus on aspects found in assessments. Washback can be positive (beneficial) or negative (harmful).

- Positive Washback: Occurs when good teaching practices result from the assessment, or when test preparation activities align with desired language learning activities. Teaching the curriculum becomes the same as teaching to the test in a beneficial way.

- Negative Washback: Happens when there’s a mismatch between instructional goals and assessment focus, leading to the abandonment of broader goals in favor of narrow test preparation. For example, if writing is tested only by multiple-choice items, teachers might prioritize practicing such items over developing actual writing skills.

The nature of the test construct (what is being tested) is crucial; a narrow construct can lead to teachers and learners restricting what they learn. The high stakes associated with tests (e.g., for student progression, teacher evaluation, school funding) often intensify the washback effect, making test preparation a central function of teaching.

The Impact of Assessment of Learning

AoL has significant implications for various stakeholders:

- Students: AoL provides evidence of their achievement and readiness for progression. However, high-stakes tests can cause stress and anxiety, and a narrow focus on tested material may not reflect their full learning.

- Teachers: AoL helps assess student achievement against outcomes and can inform future planning and instructional effectiveness. However, pressure from high-stakes testing can lead to “teaching to the test” and curriculum narrowing.

- Educational Institutions: AoL data is used for accountability, program evaluation, student placement, and demonstrating quality. However, there’s a risk of focusing on easily measurable outcomes and “gaming the system” if stakes are too high.

- Policymakers: AoL provides data for system-level monitoring, public accountability, informing policy, and international comparisons. However, data can be misused or oversimplified.

AoL in Educational Accountability Frameworks:

AoL is a cornerstone of accountability, used to evaluate the performance of students, educators, and systems. Reporting test results is the simplest form. Stronger systems link assessment information to consequential decisions, aiming to provide clear direction and motivate improvement. However, high-stakes accountability can lead to undesirable consequences like curriculum narrowing and teaching to the test, potentially punishing marginalized populations.

Challenges, Limitations, and Ethics in Assessment of Learning

Despite its utility, AoL faces several criticisms and ethical challenges:

- Common Criticisms and Limitations:

- Snapshot in Time: Often provides only a limited view of student achievement at a single point.

- Emphasis on Rote Memorization: Can prioritize recall over higher-order thinking.

- Limited Feedback for Improvement: Feedback is often just grades/scores with little diagnostic value.

- Narrowing of the Curriculum: Overemphasis on tested subjects can lead to neglect of others.

- Resource Constraints: Effective assessment requires significant time, funding, and expertise.

- Ambiguity in Outcome Definitions: Unclear outcomes lead to inconsistent assessment.

- Overemphasis on Quantitative Measures: May fail to capture qualitative skills like creativity.

- Impact of High-Stakes Testing: Can decrease student motivation, increase stress and anxiety, narrow the curriculum, and potentially increase dropout rates.

- Ethical Considerations:

- Assessment Bias: Tests can contain biases (content, item selection, format) that unfairly disadvantage certain student groups based on cultural background, language, or cognitive styles.

- Ensuring Equity: Requires culturally inclusive practices and accommodations for diverse learners.

- Maintaining Integrity: Preventing cheating, ensuring secure administration, and ethical scoring are paramount.

- Teacher Ethics: Teachers face dilemmas regarding grading fairness, confidentiality, and balancing objective evaluation with support. Cultural backgrounds and policies influence these views.

- AI-Driven Assessment Ethics: Concerns include algorithmic bias, data privacy, transparency, accuracy, and equitable access.

The Evolution and Future of Assessment of Learning

AoL is evolving with technological advancements and new pedagogical approaches:

- Technological Transformations:

- Digital Assessment Platforms: Facilitate efficient creation, administration, and scoring, but face challenges in teacher training, student engagement, accessibility, and data privacy.

- AI-Driven Analytics and Scoring: Automates scoring and provides personalized feedback, but raises ethical concerns about bias and transparency.

- VR/AR Simulations: Create immersive environments for authentic assessment of practical skills.

- Adaptive Learning and Assessment Systems: Adjust difficulty based on student performance for more precise measurement.

- Blockchain Credentialing: Offers secure, verifiable records of competencies.

- Innovative Approaches:

- Micro-credentials: Short, competency-based recognitions of specific skills, often assessed through real-life application.

- Gamification: Applies game mechanics to assessments to enhance engagement and motivation, usable for summative purposes with built-in feedback and scoring.

- Authentic/Performance-Based Tasks: Growing emphasis on tasks requiring application of knowledge in real-world scenarios.

- Emerging Trends:

- Personalized Assessment: Tailoring assessment to individual learner needs, with GenAI as a key enabler, though posing challenges to standardization and psychometric soundness.

- Integration of Formative Elements: Blurring lines between AoL, AfL, and AaL, using summative data formatively.

- Data-Informed Decision Making: Systematic use of assessment data to guide instruction, curriculum, and policy.

- Focus on 21st-Century Skills: Assessing complex skills like critical thinking, collaboration, and creativity.

More Holistic and Effective Educational Evaluation

Understanding the distinctions and interconnections between test, measurement, assessment, and evaluation is crucial for fostering effective educational environments. While tests provide specific data points and measurement quantifies these observations, assessment offers a broader, systematic approach to gathering evidence of learning. Evaluation then uses this evidence to make informed judgments that can lead to improvements at all levels of the education system.

Assessment of Learning, or summative assessment, remains a vital component for certifying achievement and ensuring accountability. However, its implementation must be guided by principles of validity, reliability, fairness, and transparency, and its potential limitations, such as the risk of curriculum narrowing or undue student stress, must be actively mitigated. The washback effect highlights the profound influence assessment has on teaching and learning, underscoring the need for assessments that promote, rather than hinder, sound pedagogical practices and deep learning.

The future of educational evaluation points towards more personalized, technologically enhanced, and integrated approaches. Innovations like AI-driven analytics, adaptive systems, and authentic performance tasks offer exciting possibilities for creating more nuanced and meaningful assessments. However, these advancements also bring new ethical challenges, particularly concerning bias, privacy, and equity, which demand careful consideration and robust safeguards.

Ultimately, the goal is to create a balanced assessment system where summative evaluations are complemented by rich formative and student-led assessment practices. By aligning assessment methods with clear learning objectives, leveraging technology responsibly, and fostering assessment literacy among all stakeholders, we can ensure that test, measurement, assessment, and evaluation work synergistically to not only measure learning but also to enhance it, preparing learners for success in an ever-evolving world.

[…] A third pioneer was E.L. Thorndike (1874–1949), who initiated an emphasis on assessment and measurement. […]

[…] third pioneer was E.L. Thorndike (1874-1949), who initiated an emphasis on assessment and measurement. He promoted the scientific underpinnings of learning. He argued that one of schooling’s most […]