1. Foundations of the CIPP Evaluation Model

The Context, Input, Process, Product (CIPP) model stands as a significant and enduring framework in the field of educational evaluation. Its development in the 1960s marked a pivotal shift towards more comprehensive, improvement-oriented, and decision-focused evaluation practices. Understanding its origins, the socio-educational climate of its inception, and its core philosophical tenets is crucial for appreciating its unique contributions and lasting relevance.

1.1. Genesis: Daniel Stufflebeam and the Call for Improvement-Oriented Evaluation

The CIPP model was conceptualized and developed by Daniel L. Stufflebeam and his colleagues in the 1960s. Stufflebeam, a distinguished figure in educational evaluation, envisioned a holistic framework that would transcend the limitations of prevailing evaluation approaches. His primary aim was to create a model that systematically collects and analyzes information not merely for summative judgment but for proactive program management, continuous improvement, and informed future planning.

A central point of Stufflebeam’s philosophy, embedded deeply within the CIPP model, is that evaluation’s most important purpose is “not to prove, but to improve”. This guiding principle represented a significant departure from evaluation methodologies that were predominantly focused on measuring the attainment of pre-specified objectives, often through standardized testing and experimental designs, which were common at the time. Stufflebeam perceived a critical need for evaluation to be an integral part of the program development and implementation lifecycle, providing timely and relevant feedback to decision-makers at various stages. This proactive stance contrasts sharply with reactive evaluation approaches that primarily deliver a judgment after a program. The CIPP model, therefore, was designed to be a dynamic tool, fostering a “learning-by-doing” approach to program enhancement, where evaluation findings continuously inform adjustments and refinements. This inherent focus on ongoing development underscores the model’s commitment to making programs better, rather than simply labeling them as successes or failures after the fact.

1.2. Historical Context: Responding to 1960s Educational Reforms and Accountability Demands

The CIPP model did not emerge in a vacuum; its development was a direct response to the specific societal and educational dynamics of the 1960s in the United States. This era was characterized by substantial federal investment in education and social programs, largely driven by initiatives such as President Lyndon B. Johnson’s “War on Poverty” and the passage of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) of 1965. ESEA, particularly its Title I component, channeled significant funding towards improving educational opportunities for disadvantaged students, often in urban and inner-city school districts.

This unprecedented level of federal involvement brought with it a heightened demand for accountability. Policymakers and the public sought assurance that these substantial investments were yielding tangible results and that programs were being implemented effectively. Traditional evaluation models, often narrowly focused on quantifiable objectives, were perceived as inadequate for assessing the multifaceted and complex nature of these new large-scale social and educational interventions. The CIPP model, with its comprehensive framework, was developed to address these limitations. It offered a systematic methodology for providing timely evaluative information that could serve both proactive decision-making for program improvement and retroactive assessments for accountability. The model’s capacity to examine the broader context of interventions, the resources allocated, the intricacies of implementation, and the full spectrum of outcomes made it particularly well-suited to the complex challenges of evaluating the ambitious educational reforms of the 19s. Thus, the CIPP model was forged in an environment that demanded more than simple measurement; it required a framework that could navigate the complexities of systemic change and provide meaningful insights for both ongoing management and public accountability.

1.3. Core Philosophy: Decision-Focused and Improvement-Driven Evaluation

At its heart, the CIPP model is fundamentally a decision-focused and improvement-driven approach to evaluation. Its design emphasizes the systematic collection, analysis, and provision of information specifically for program management and operational decision-making. The guiding philosophy is that evaluation is most valuable when it directly addresses the informational needs of those responsible for making decisions about a program, thereby enhancing the quality and effectiveness of those decisions.

The CIPP framework operationalizes this philosophy through a cyclical process encompassing planning, structuring, implementing, and reviewing/revising decisions. Unlike models that may deliver findings only at the end of a program, CIPP is designed to provide continuous feedback throughout a program’s lifecycle. This iterative process ensures that evaluation is not an isolated event but an ongoing dialogue that informs and refines program activities. The model posits that evaluation should serve decision-making, and to do so effectively, it must understand the decisions that need to be serviced and project the kinds of information that will be most useful.

This decision-focused and improvement-driven orientation recasts the role of the evaluator. Instead of acting solely as an external judge rendering a final verdict, the evaluator becomes a facilitator of informed action, an active partner in the program’s journey towards achieving its goals and maximizing its positive impact. The emphasis is on the utility and relevance of evaluation findings; evaluation is not an end in itself but a critical means to achieving better program processes and outcomes. This pragmatic approach values the timeliness and applicability of information, ensuring that evaluation efforts contribute directly to the betterment of the program being assessed.

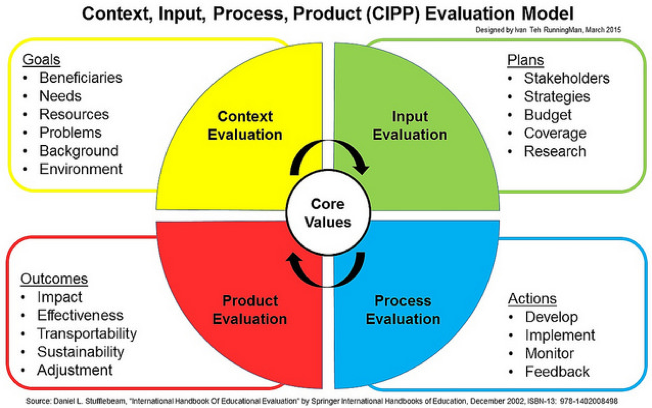

2. Deconstructing the CIPP Model: The Four Pillars of Comprehensive Evaluation

The CIPP model is structured around four interconnected types of evaluation—Context, Input, Process, and Product—each designed to answer distinct sets of questions and provide specific kinds of information crucial for decision-making at different stages of a program’s lifecycle. A detailed examination of these components reveals the model’s comprehensive and systematic approach to understanding and improving educational curricula and programs.

2.1. Context Evaluation: Assessing Needs, Problems, Assets, and Opportunities

Context Evaluation forms the initial and arguably most critical pillar of the CIPP model. Its primary function is to assess the needs, problems, assets, and opportunities within a defined environment or setting. This phase directly addresses the fundamental question: “What should we do?” or “What needs to be done?”. It involves a thorough collection and analysis of needs assessment data to establish or refine program goals, priorities, and objectives. The process includes defining the existing environment (both actual and desired), identifying unmet needs and untapped opportunities, and diagnosing underlying problems or barriers that might impede progress.

Methodologically, context evaluation can employ a range of techniques, including conceptual analysis to define the target population, empirical studies (such as surveys and demographic analyses) to identify needs and opportunities, and the solicitation of judgments from experts, clients, and other stakeholders regarding barriers, problems, and desired goals. The information sought is broad, encompassing background data on beneficiary needs and assets (e.g., from health records, school data, funding proposals), stakeholder perspectives, details about the program’s operating environment (including related programs, community resources, and political dynamics), and a critical assessment of program goals against the identified needs and assets. For instance, a context evaluation for a new literacy program might involve analyzing current literacy achievement scores, existing literacy policies, concerns voiced by teachers and community members, and the specific needs of the target student population.

The thoroughness of context evaluation serves as the foundational anchor for the entire evaluation and the program itself. If the needs, problems, assets, and opportunities are not accurately identified and deeply understood at this stage, all subsequent evaluation efforts—Input, Process, and Product—risk being misdirected. More critically, the program itself may lack relevance or fail to achieve its intended impact if its foundational goals are not well-aligned with the actual context. Thus, the rigor applied during context evaluation significantly influences the validity and utility of the entire programmatic endeavor.

2.2. Input Evaluation: Examining Resources, Strategies, and Proposed Plans

Following the establishment of a clear understanding of the context and program goals, Input Evaluation focuses on assessing competing strategies, alongside the work plans and budgets of the selected approach. This component addresses the question, “How should it be done?”. It involves identifying the necessary steps and resources—material, temporal, physical, and human—required to meet the established goals and objectives. This may include researching and identifying successful external programs or materials that could serve as models or be adapted.

A key function of input evaluation is to assess the proposed program strategy for its responsiveness to the needs identified in the context phase, as well as its overall feasibility—scientifically, economically, socially, politically, and technologically. Information sought includes details of existing model programs, comprehensive descriptions of the program’s proposed strategy, work plan, and budget, and critical assessments of the strategy’s feasibility and alignment with identified needs. Comparisons with relevant research literature and alternative strategies employed in similar programs are also integral to this phase.

Input evaluation serves as a form of proactive risk management and strategic planning. It moves beyond a simple inventory of available resources to a critical examination of the viability and optimality of the chosen program design and resource allocation plan. By rigorously evaluating alternative approaches and the feasibility of the selected strategy, input evaluation aims to prevent the misallocation of resources into poorly conceived or unsustainable initiatives. The thoroughness of this stage is vital for maximizing the efficient use of resources and increasing the likelihood of program success. Stufflebeam regarded input evaluation as a frequently neglected yet critically important type of evaluation, underscoring its strategic role in laying a sound foundation for program implementation.

2.3. Process Evaluation: Monitoring and Documenting Program Implementation and Activities

Once a program is underway, Process Evaluation comes to the fore, focusing on monitoring, documenting, and assessing program activities and implementation. This component directly addresses the question, “Is it being done as planned?”. Its purpose is to provide decision-makers with ongoing information about the fidelity of implementation, adherence to plans and guidelines, emerging conflicts or challenges, staff support and morale, and the strengths and weaknesses of materials, delivery methods, and budgetary execution.

Process evaluation is crucial for providing continuous feedback that can be used to refine and improve the program while it is in progress. This makes it a cornerstone of continuous quality improvement efforts. Information sought includes records of program events, encountered problems, incurred costs, resource allocations, direct observations of program activities, progress reports, and assessments of program progress from beneficiaries, program leaders, and staff through methods like interviews and surveys.

This component is the primary engine through which the CIPP model facilitates formative evaluation and adaptive management. It is not merely a compliance check; rather, it is an active investigation into the dynamics of program implementation. By systematically tracking activities and gathering feedback, process evaluation allows for the early detection of deviations from the plan, unforeseen obstacles (which may arise from changes in context or inadequacies in input planning), or areas where the program is excelling. This information enables timely mid-course corrections, ensuring that the program remains on track to achieve its objectives or can be effectively adapted to changing realities. The emphasis on continuous monitoring and feedback is central to CIPP’s philosophy of evaluation as a tool for ongoing improvement.

2.4. Product Evaluation: Measuring, Interpreting, and Judging Outcomes and Impact

The final pillar, Product Evaluation, assesses program outcomes, encompassing both intended and unintended effects, and considering both short-term and long-term consequences. It seeks to answer the critical question, “Did it succeed?” or “Is it succeeding?”. This phase involves measuring the actual outcomes and comparing them to the anticipated outcomes, as well as to the needs identified during context evaluation, to help decision-makers determine whether the program should be continued, modified, or discontinued. Stufflebeam’s CIPP Evaluation Model Checklist further refines product evaluation into four sub-components: impact, effectiveness, sustainability, and transportability. This comprehensive assessment aims to judge a program’s merit (quality), worth (meeting needs), significance (importance), and probity (integrity).

Key questions addressed within product evaluation include:

- Impact: Were the right beneficiaries reached?

- Effectiveness: Were their needs met? Were program objectives achieved?

- Sustainability: Were the gains for beneficiaries sustained over time? Can the program continue effectively?

- Transportability: Did the processes that produced the gains prove transportable and adaptable for effective use in other settings? Information sought includes quantitative and qualitative data on outcomes, stakeholder judgments on program effects, in-depth case studies of beneficiaries, comparisons with similar programs, and assessments of long-term implementation and continuing need or demand.

Product evaluation within the CIPP framework represents a multi-dimensional value judgment that extends beyond a simple measurement of whether pre-stated objectives were achieved. The inclusion of impact, effectiveness, sustainability, and transportability provides a much richer and more nuanced understanding of a program’s overall value and its potential for broader application or long-term success. For example, a program might effectively meet its immediate objectives for participants but fail to reach the most needy segment of the target population (low impact), or its positive effects might diminish rapidly once program support is withdrawn (low sustainability). This comprehensive perspective allows for more informed and strategic decisions regarding a program’s overall worth, its future direction, and potential for replication or scaling. This detailed approach to outcomes also feeds back into the improvement cycle, providing valuable lessons for future program design and implementation.

The following table summarizes the core aspects of each CIPP component:

Table 1: The CIPP Model Components: Purpose, Key Questions, and Information Sought

| Component | Core Question Addressed | Purpose | Key Questions to Address (Examples) | Types of Information Sought (Examples) |

| Context | What needs to be done? | To assess needs, problems, assets, and opportunities to establish or clarify goals, priorities, and objectives. | What are the unmet needs of the target population? What existing assets can be leveraged? What are the underlying problems? Are current goals aligned with needs? What is the socio-political environment? | Needs assessment data, demographic data, stakeholder interviews, policy documents, community profiles, literature reviews on similar contexts. |

| Input | How should it be done? | To assess competing strategies, resources, and action plans for feasibility and potential effectiveness. | What alternative strategies exist? Is the proposed plan and budget feasible and adequate? Are resources (human, financial, material) sufficient? Is the strategy responsive to needs? | Program plans, budgets, staffing plans, resource inventories, research on alternative approaches, feasibility studies, cost-benefit analyses. |

| Process | Is it being done? | To monitor, document, and assess program implementation activities for fidelity and continuous improvement. | Is the program being implemented as planned? What activities are occurring? Are there implementation barriers? How are participants engaging? Is feedback being utilized? | Implementation logs, observation records, participant feedback, staff interviews, progress reports, documentation of activities and deviations from plan. |

| Product | Did it succeed? | To identify and assess outcomes (intended and unintended, short-term and long-term) and overall impact. | Were program objectives met? What was the impact on beneficiaries? Were there unintended outcomes? Is the program effective in meeting needs? Is it sustainable? Is it transportable? | Outcome data (quantitative and qualitative), stakeholder judgments, case studies, comparison with control/comparison groups (if applicable), cost-effectiveness data, long-term follow-up data. |

| Impact (Sub) | Were the right beneficiaries reached? | To assess the program’s reach to the target audience and coverage of needs. | Who was served by the program? Did the program reach the intended individuals/groups? Were important community needs addressed? | Participant demographics, service delivery records, community feedback. |

| Effectiveness (Sub) | Were their needs met? | To document and assess the quality and significance of outcomes in meeting identified needs. | How well were beneficiary needs met? What was the quality of the outcomes? Were there positive and negative effects? | Pre/post assessments, stakeholder satisfaction surveys, performance indicators, case studies of impact. |

| Sustainability (Sub) | Were the gains sustained? | To assess the extent to which a program’s contributions are institutionalized and continued over time. | Are program benefits likely to continue after initial funding/support ends? Are there plans and resources for continuation? Is there ongoing need/demand? | Follow-up assessments, institutionalization plans, budget allocations for continuation, evidence of continued need. |

| Transportability (Sub) | Is it adaptable elsewhere? | To assess the extent to which a program could be successfully adapted and applied in other settings. | Could this program be replicated in other contexts? What adaptations would be needed? What factors are critical for successful replication? | Documentation of program model and critical components, feedback from potential adopters, results of pilot implementations in new settings. |

3. The CIPP Model Diverse Applications and Illustrative Case Studies

The CIPP model’s robust and flexible framework has led to its widespread application across a multitude of educational settings and for evaluating diverse types of programs and curricula. Its capacity to provide a comprehensive view, from initial needs assessment to final impact, makes it a valuable tool for educators, administrators, and policymakers seeking to understand and enhance educational effectiveness.

3.1. Evaluating K-12 Curricula and Programs

In the K-12 sector, the CIPP model has been employed to evaluate overall educational quality at the school level, as well as specific curricular programs and interventions. For instance, studies have utilized CIPP to assess a 5th-grade English curriculum, the efficacy of reading Response to Intervention (RtI) models, the implementation of standards-based grading systems, and the effectiveness of child-friendly school programs. Furthermore, its application extends to specialized areas such as the evaluation of portfolio assessment in science learning and project-based assessments in topics like optics.

These varied applications demonstrate CIPP’s utility in dissecting different facets of K-12 education. When evaluating a child-friendly school program, for example, the Context evaluation might scrutinize the alignment of program goals with national child welfare policies and local community needs. The Input evaluation would then assess the adequacy of teacher training, resource availability, and parental involvement strategies. Process evaluation would monitor the actual implementation of child-friendly pedagogical practices, disciplinary approaches, and the creation of a supportive school environment. Finally, Product evaluation would measure the program’s impact on students’ holistic development, including academic, social, and emotional well-being, as well as changes in school climate.55 The model’s adaptability allows it to be scaled appropriately, whether for a system-wide review of educational quality or a focused assessment of a single classroom intervention, making it a versatile instrument for continuous improvement in K-12 settings.

3.2. Application in Higher Education Program Review and Enhancement

The CIPP model is also extensively used in higher education for comprehensive program reviews and ongoing enhancement efforts. It has been applied to evaluate a wide array of programs, including Bachelor of Education (BEd) programs , leadership development programs for medical fellows , various graduate programs , medical school curricula , and specialized programs like dentistry competency-based evaluations and university-level traffic safety courses.

In these higher education contexts, the CIPP framework guides a systematic examination of program relevance, resource adequacy, process effectiveness, and outcome achievement. For instance, in the evaluation of a BEd program, Context evaluation would assess the program’s alignment with national educational blueprints, societal demands for qualified teachers, and the evolving needs of students entering the teaching profession. Input evaluation would scrutinize the curriculum design, the qualifications and expertise of faculty, the availability of teaching practice opportunities, and library and technology resources. Process evaluation would monitor teaching methodologies, student engagement, the quality of supervision during practicums, and feedback mechanisms. Product evaluation would then assess graduate teacher competency, employability, impact on student learning in schools, and overall program satisfaction. The comprehensive nature of CIPP aligns well with the rigorous demands of quality assurance and accreditation processes prevalent in higher education, which necessitate evidence of systematic review and continuous improvement across all program dimensions. The model’s capacity to inform critical decisions regarding program continuation, modification, or termination is particularly valuable for strategic planning and resource allocation within universities and colleges.

3.3. Use in Vocational Education and Training Program Assessment

Vocational education and training (VET) programs have also benefited significantly from the application of the CIPP model. The model is frequently used to assess the effectiveness of VET curricula, including specific components like student internship programs. Its systematic approach allows for a clear depiction of program conditions and provides a solid basis for actionable recommendations.

Within VET, Context evaluation is crucial for ensuring that curricula are aligned with current and future industry needs and labor market demands. Input evaluation examines the adequacy of training facilities, equipment, materials, and the expertise of instructors and trainers. Process evaluation monitors the delivery of hands-on training, the effectiveness of pedagogical approaches (such as work-based learning), and the engagement of trainees. Product evaluation then assesses graduates’ skill acquisition, employability, on-the-job performance, and the overall impact of the training on their career progression. The CIPP model’s strength in this domain lies in its ability to forge clear links between vocational education provision and the dynamic requirements of the workplace. By systematically evaluating how well programs prepare individuals for specific occupations and adapt to evolving industry standards, CIPP helps ensure the relevance and economic value of vocational training. However, the effectiveness of such evaluations can be contingent on the evaluators’ ability to conduct in-depth analyses that go beyond surface-level assessments, requiring expertise in both the CIPP framework and the specific vocational field under review.

3.4. Adapting CIPP for Online, Blended, and Technology-Enhanced Learning Environments

The proliferation of online, blended, and technology-enhanced learning environments has presented new challenges and opportunities for program evaluation, and the CIPP model has demonstrated its adaptability in these contexts. It has been successfully applied to evaluate online English learning programs implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, assess the quality of blended teaching in higher education , evaluate e-learning based life skills training programs, and examine virtual learning initiatives in health professions education during the pandemic.

In these technology-mediated settings, the CIPP components are tailored to address unique aspects. Context evaluation might explore the rationale for adopting online or blended models, student and faculty readiness for technology, and the broader digital infrastructure. Input evaluation would assess the suitability of learning management systems, digital content, online assessment tools, and technical support services. Process evaluation monitors the effectiveness of virtual teaching strategies, online student engagement and interaction, the usability of technology platforms, and the quality of online facilitation. Product evaluation measures learning outcomes achieved in the online or blended format, student and faculty satisfaction, and the cost-effectiveness of the technological approach. The fundamental questions posed by CIPP—What needs to be done? How should it be done? Is it being done effectively? Did it succeed?—provide a stable and robust framework for inquiry, even as the specific variables and data points within each component evolve with technological advancements. This inherent structural consistency allows CIPP to guide evaluations effectively in novel and rapidly changing educational technology landscapes, including those involving emerging technologies like AI and VR.

3.5. Evaluating Inclusive Education and Competency-Based Programs

The CIPP model’s comprehensive nature also lends itself well to the evaluation of specialized educational approaches such as inclusive education and competency-based programs. It has been utilized to assess the implementation of inclusive education curricula in settings like Madrasah Aliyah (Islamic senior high schools) and to evaluate competency-based assessment programs in fields like dentistry.

When applied to inclusive education, Context evaluation helps determine if the school’s vision, mission, policies, and overall environment are conducive to meeting the diverse needs of all learners, including those with special needs. Input evaluation assesses the availability of specialized staff, adapted materials, assistive technologies, and appropriate professional development for teachers. Process evaluation monitors the implementation of inclusive pedagogical practices, differentiation strategies, collaborative teaching, and the social integration of students with special needs. Product evaluation then examines the academic progress, skill development, and social-emotional well-being of all students, paying particular attention to equitable outcomes.

Similarly, in competency-based education, Context evaluation would clarify the specific competencies to be developed and their relevance to professional standards or future roles. Input evaluation would assess the curriculum design, learning resources, and assessment tools designed to foster and measure these competencies. Process evaluation would monitor how effectively teaching and learning activities facilitate competency development and how assessments are administered. Product evaluation would then measure the extent to which students have achieved the defined competencies and their ability to apply them in relevant contexts. The CIPP model’s emphasis on clearly defining needs and assessing outcomes for all targeted beneficiaries makes it a particularly strong framework for evaluations focused on equity and the attainment of specific, measurable skills and abilities. Challenges noted in some studies regarding the optimal fulfillment of product components in inclusive settings underscore the complexities involved in achieving and measuring equitable outcomes, a task for which CIPP can provide structure but requires careful and nuanced application.

The following table illustrates the diverse applications of the CIPP model:

Table 2: Examples of CIPP Model Application Across Educational Settings

| Educational Setting | Specific Program/Curriculum Evaluated | Key Focus of CIPP Application |

| K-12 Education | Child-Friendly School Program | Assessed alignment with policies (Context), resources & teacher training (Input), non-violent discipline & democratic practices (Process), and holistic student development (Product). |

| 5th Grade English Curriculum | Evaluated curriculum objectives, teaching materials, instructional processes, and student learning outcomes in English. | |

| Science Learning Portfolio Assessment | Developed and validated a CIPP-based instrument to evaluate the implementation of portfolio assessment in science learning. | |

| Higher Education | Bachelor of Education (BEd) Program | Evaluated program goals against national standards & student needs (Context), curriculum design & faculty (Input), teaching methods & student engagement (Process), and graduate outcomes & impact (Product). |

| Dentistry Competency-Based Evaluation Program | Assessed departmental atmosphere for new methods (Context), faculty/student familiarity with methods (Input), faculty cooperation in implementation (Process), and impact on practical learning & ethics (Product). | |

| Leadership in QI Program for Medical Fellows | Used CIPP to evaluate a leadership program, providing targeted feedback for improving decisions across context, input, process, and product stages. | |

| Vocational Education & Training | Vocational Education Programs (General) | Assessed relevance to industry needs (Context), training resources & instructor expertise (Input), effectiveness of hands-on training (Process), and graduate employability & skill application (Product). |

| Vocational College Students’ Internship Programs | Optimized internship management by evaluating alignment with institutional/societal needs (Context), resource support (Input), process management (Process), and overall effectiveness (Product). | |

| Online/Blended/EdTech Environments | Online English Learning Programs (COVID-19) | Evaluated program objectives in pandemic context (Context), technology access & student tech mastery (Input), online engagement & interaction (Process), and learning outcomes in remote setting (Product). |

| Virtual Learning in Health Professions (COVID-19) | Assessed university support for internet costs (Input), suitability of virtual teaching methods (Process), and impact on student creativity and time-saving aspects (Product) within the pandemic context. | |

| Inclusive & Competency-Based Education | Inclusive Education Curriculum in Madrasah Aliyah | Assessed school vision for inclusion (Context), availability of special education personnel & facilities (Input), responsive interaction patterns (Process), and skill improvement of students with special needs (Product). |

4. Analytical Perspectives on the CIPP Model

A thorough understanding of the CIPP model necessitates a critical examination of its inherent strengths and acknowledged limitations, as well as a comparative analysis with other prominent evaluation frameworks. Such perspectives provide a nuanced appreciation of CIPP’s position and utility within the broader landscape of educational evaluation.

4.1. Strengths and Advantages: Why CIPP Endures

The CIPP model has maintained its relevance and widespread use for several decades due to a confluence of inherent strengths that address fundamental needs in program evaluation.

One of its primary advantages is its comprehensive and holistic nature. By systematically examining Context, Input, Process, and Product, the CIPP model provides a panoramic view of a program, ensuring that all critical aspects are considered. This thoroughness allows evaluators to move beyond simplistic outcome measures to understand the complex interplay of factors that contribute to program success or failure.

The model’s decision-oriented and improvement-focused philosophy is another significant strength. It is explicitly designed to provide useful information to decision-makers at all stages of a program, facilitating ongoing adjustments and strategic planning. This dual utility for both formative (improvement-oriented) and summative (judgment-oriented) evaluation makes CIPP highly versatile.

Furthermore, the CIPP model is recognized for its flexibility and adaptability. It was not conceived for any single type of program or solution, allowing its four core components to be applied as a whole or selectively to suit diverse evaluation needs and contexts. This adaptability is enhanced by the model’s emphasis on stakeholder involvement, which encourages participation from various groups in affirming values, defining evaluation questions, contributing information, and assessing reports, thereby increasing the relevance and utility of the findings. Finally, the availability of clear guidance, including detailed checklists and frameworks developed by Stufflebeam and colleagues, facilitates its practical application.

The interconnectedness of these strengths is significant. The model’s comprehensiveness directly supports its decision-and-improvement focus; by examining all program phases, it furnishes nuanced information crucial for varied decisions at different junctures, encompassing both formative and summative evaluation needs. This holistic perspective, in turn, underpins its adaptability, as different facets of the model can be emphasized depending on the specific purpose of the evaluation and the developmental stage of the program.

4.2. Limitations, Criticisms, and Practical Challenges

Despite its considerable strengths and widespread adoption, the CIPP model is not without limitations and has faced certain criticisms and practical challenges in its implementation.

A primary challenge stems from its complexity and resource intensity. Conducting a full CIPP evaluation, encompassing all four components in depth, can be a time-consuming, costly, and intricate undertaking. It often requires significant investment in terms of time, funding, and skilled personnel. This inherent demand can be a barrier, particularly for organizations or projects with limited resources.

Related to this, there is a potential for superficial analysis if evaluators lack the expertise or resources to delve deeply into each component. Some studies have noted instances where evaluators were unable to provide in-depth analysis of identified problems, leading to evaluations that remained at a surface level rather than uncovering root causes or offering robust solutions. The quality and depth of a CIPP evaluation are thus heavily reliant on the skills, experience, and diligence of the evaluation team.

Another point of discussion is the potential overlap between Context evaluation and traditional needs assessment, which some argue can lead to blurred lines or redundancy if not clearly delineated. While Context evaluation is broader, encompassing assets and opportunities beyond just needs, careful planning is required to ensure its distinct contribution.

Furthermore, the CIPP model has been critiqued by some for its perceived managerial or top-down orientation. Critics suggest that its decision-focused nature might prioritize the information needs of administrators and policymakers, potentially overlooking grassroots perspectives or the complex, often messy political realities of program implementation if stakeholder engagement is not genuinely and broadly pursued.

Finally, a more nuanced critique points to a limitation in the CIPP model’s capacity for “confirmative evaluation”—that is, evaluating the continued value and relevance of a program long after its initial implementation and summative assessment, particularly in determining if it should be sustained or if its core value has been “confirmed” over time. While CIPP includes sustainability in its Product evaluation, the concept of confirmative evaluation suggests a longer-term, ongoing validation that some argue is not fully elaborated within the standard CIPP framework.

The model’s comprehensiveness, while a significant strength, paradoxically gives rise to its most notable practical challenge: the substantial resources and expertise required for its full and effective application. This creates an inherent tension between the ideal, exhaustive use of the CIPP model and the pragmatic constraints often encountered in real-world evaluation settings.

4.3. Comparative Insights: CIPP alongside Tyler’s, Stake’s, and Scriven’s Models

To fully appreciate the CIPP model’s unique contributions and characteristics, it is instructive to compare it with other influential evaluation frameworks, notably Ralph Tyler’s Objectives-Centered Model, Robert Stake’s Countenance/Responsive Model, and Michael Scriven’s Goal-Free Evaluation.

CIPP vs. Tyler’s Objectives-Centered Model:

Ralph Tyler’s model, a cornerstone of early curriculum evaluation, primarily focuses on determining the extent to which pre-determined educational objectives are achieved by the program.81 Evaluation is a direct comparison between intended and actual results. In contrast, the CIPP model offers a significantly more comprehensive and systemic view, examining not only the products or outcomes but also the context in which the program operates, the inputs (resources and plans) utilized, and the processes of implementation. While Tyler’s model has been criticized for providing limited mechanisms for feedback and program improvement during its lifecycle, CIPP is explicitly designed for this purpose, embedding formative evaluation throughout its stages. Tyler’s approach is generally considered simpler and more straightforward, making it potentially easier to implement when objectives are clear and stable. However, this simplicity can also be a limitation, as it may not adequately address programs with evolving objectives or complex, unintended outcomes. CIPP, being more intricate, is better equipped to handle such complexities and provides a more detailed, multi-stage evaluation. In many respects, CIPP can be viewed as an evolution from purely objective-driven evaluation, addressing the need to understand not just if objectives were met, but why certain outcomes occurred and how programs can be systematically improved.

CIPP vs. Stake’s Countenance/Responsive Model:

Robert Stake’s Countenance Model, and his later emphasis on Responsive Evaluation, prioritizes a deep, descriptive understanding of a program, taking into account the diverse perspectives and concerns of various stakeholders. It is characterized by its qualitative nature and its flexibility, often allowing evaluation questions and foci to emerge organically as the evaluator interacts with the program and its participants. While CIPP also values stakeholder input and can incorporate qualitative methods, it generally presents a more structured, preordinate framework designed to provide systematic information for managerial decision-making. Stake’s approach is more pluralistic, emphasizing the understanding of program activities and unique site-specific issues, often more so than the program’s stated intents. CIPP, while comprehensive, tends to be more aligned with a managerial perspective focused on program improvement and accountability against defined goals and needs. The two models represent different, though potentially complementary, evaluation philosophies: CIPP offers a systematic, component-based framework, while Stake’s model champions a more adaptive, issue-driven, and deeply contextualized responsiveness. The perceived “top-down” nature of CIPP in some applications contrasts with the inherently more emergent and stakeholder-centered approach of responsive evaluation.

CIPP vs. Scriven’s Goal-Free Evaluation (GFE):

Michael Scriven’s Goal-Free Evaluation (GFE) proposes that evaluators should intentionally remain unaware of a program’s stated goals and objectives to avoid “tunnel vision” and focus instead on identifying all actual effects of the program, both intended and unintended.1 This approach aims to provide a more objective assessment of what a program is actually doing and achieving. The CIPP model, particularly in its Context Evaluation phase, typically involves understanding and often clarifying program goals. Its Product Evaluation component then assesses outcomes, ideally in relation to these goals, although it also explicitly calls for the assessment of unintended outcomes.11 Scriven himself has suggested that GFE can serve as a valuable supplement to goal-oriented frameworks. While CIPP is not inherently goal-free, its comprehensive nature, especially in the Product phase, can be enhanced by incorporating GFE principles. An evaluator using CIPP could consciously adopt a goal-free stance during certain data collection and analysis stages of Product evaluation to ensure a broader discovery of all program effects, thereby mitigating potential bias from an overemphasis on pre-stated objectives and strengthening the overall objectivity of the CIPP evaluation.

The following tables provide a comparative overview and a summary of the CIPP model’s characteristics:

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Key Evaluation Models

| Feature | CIPP Model (Stufflebeam) | Tyler’s Objectives-Centered Model | Stake’s Countenance/Responsive Model | Scriven’s Goal-Free Evaluation (GFE) |

| Developer(s) | Daniel Stufflebeam & colleagues | Ralph Tyler | Robert Stake | Michael Scriven |

| Primary Focus/Purpose | Comprehensive program improvement and decision-making; accountability. | Determine if pre-defined objectives are met. | Understand program activities, issues, and diverse stakeholder perspectives; description & judgment. | Identify all actual program effects (intended and unintended) without reference to stated goals. |

| Key Strengths | Holistic; systematic; supports formative & summative evaluation; decision-oriented; flexible. | Simple; clear; directly measures objective attainment. | Responsive to context & stakeholders; rich descriptions; uncovers unique issues. | Reduces goal-related bias; uncovers unintended outcomes; adaptable. |

| Key Weaknesses/Limitations | Can be complex & resource-intensive; potential for superficiality if not applied rigorously; perceived as managerial. | Narrow focus on objectives; may miss unintended outcomes; less flexible for evolving programs. | Can be time-consuming; evaluator role may be ambiguous; findings may lack generalizability. | Lacks clear operational guidelines; theoretically abstract; typically supplemental. |

| Typical Application Context | Wide range of educational programs, projects, systems; K-12, higher ed, vocational, online learning. | Curricula with clear, stable, measurable objectives. | Evaluations requiring deep understanding of specific program contexts and stakeholder views. | Supplementing goal-based evaluations; situations with unclear or contested goals. |

Table 4: Summary of CIPP Model Strengths and Limitations

| Strengths of CIPP Model | Limitations/Criticisms of CIPP Model |

| Comprehensive & Holistic: Evaluates Context, Input, Process, and Product, providing a full picture of the program. | Complexity & Resource Intensity: Full application can be time-consuming, costly, and require significant expertise and resources. |

| Decision-Oriented & Improvement-Focused: Primarily aims to provide information for better decision-making and continuous program improvement. | Potential for Superficial Analysis: Risk of surface-level evaluation if evaluators lack depth or resources for thorough investigation of each component. |

| Formative & Summative Utility: Applicable for ongoing monitoring and adjustments (formative) as well as final judgments of merit and worth (summative). | Overlap with Needs Assessment: Context evaluation may sometimes appear similar to standard needs assessment, requiring clear differentiation. |

| Flexibility & Adaptability: Can be tailored to diverse programs, contexts, and evaluation questions; components can be used selectively. | Managerial/Top-Down Perception: Can be viewed as overly managerial if stakeholder engagement is not genuinely and broadly implemented, potentially overlooking complex political realities. |

| Stakeholder Involvement: Actively encourages participation of diverse stakeholders, enhancing relevance and utility. | Lack of “Confirmative Evaluation” Focus: Some argue it falls short in explicitly guiding long-term confirmative evaluation of sustained program value. |

| Clear Guidance & Structure: Supported by detailed frameworks, checklists, and a long history of application. |

5. Navigating Complexity and Ensuring Rigor in CIPP Evaluations

The comprehensive nature of the CIPP model, while one of its greatest strengths, also presents practical challenges related to complexity, resource demands, and the potential for bias. Effectively navigating these challenges is crucial for conducting rigorous and meaningful CIPP evaluations. This involves strategic implementation, a commitment to objectivity, and robust engagement with values, ethics, and stakeholders.

5.1. Strategies for Managing Resource Intensity and Complexity

The thoroughness inherent in evaluating all four CIPP components—Context, Input, Process, and Product—can make full-scale applications resource-intensive in terms of time, budget, and personnel. However, the model itself offers flexibility to manage this. Stufflebeam emphasized that the CIPP components can be employed selectively, in various sequences, and often simultaneously, depending on the specific questions and needs of a particular evaluation. This means evaluators are not obligated to rigidly implement all four stages with equal depth in every instance; rather, they can focus on the components most relevant to the evaluation’s purpose and the program’s lifecycle stage.

For example, a newly conceptualized program might benefit most from intensive Context and Input evaluations to ensure its goals are relevant and its design is sound. Conversely, an established program facing implementation challenges might prioritize Process evaluation to identify bottlenecks and areas for refinement, followed by Product evaluation to assess outcomes. Leveraging existing data, employing efficient data collection methods (including technology where appropriate), and clearly defining the scope of the evaluation through contractual agreements at the outset are also critical strategies.14 Strategic selectivity in applying CIPP components, guided by clear objectives and pragmatic considerations, is thus a key to making the model feasible and effective in diverse real-world settings. This pragmatic approach allows the model to be adapted to varying resource constraints without sacrificing its core evaluative functions.

5.2. Addressing Potential for Evaluator Bias and Ensuring Objectivity

Ensuring objectivity and mitigating evaluator bias are paramount in any credible evaluation. The CIPP model incorporates several mechanisms to support these goals. It is grounded in an objectivist orientation, which strives for precise conclusions free from undue human subjective feelings by controlling for bias, prejudice, and conflicts of interest, and by validating findings from multiple sources.

One key structural element for ensuring quality and objectivity is metaevaluation—the evaluation of the evaluation itself.7 This involves assessing the evaluation’s design, conduct, and reporting against pertinent professional standards, such as the Joint Committee Program Evaluation Standards. Conducting metaevaluations, ideally including independent assessments, helps identify and correct potential flaws or biases in the evaluation process itself.

Other strategies embedded within or complementary to the CIPP framework include the systematic use of multiple data sources and methods (triangulation) to corroborate findings; the clear articulation of the values and criteria that will guide judgments; transparent reporting of methods and findings; and structured processes for stakeholder review and feedback on draft reports. For instance, requiring evaluators to provide evidence to justify ratings or conclusions, similar to practices in performance evaluation, can enhance objectivity. Furthermore, the CIPP checklist suggests the possibility of engaging a goal-free evaluator for certain aspects of the Product evaluation to provide an assessment of actual outcomes independent of stated program goals, thereby offering another layer of bias reduction. Through these procedural safeguards and a commitment to rigorous methodology, the CIPP model aims to produce defensible and trustworthy evaluation judgments.

5.3. The Role of Values, Ethics, and Stakeholder Engagement

The CIPP model explicitly recognizes that sound evaluations must be grounded in clearly articulated and appropriate values and criteria. Values, defined as principles or qualities held to be intrinsically good or desirable, inform the standards against which a program’s merit and worth are judged. The model calls for evaluators and clients to collaboratively identify and clarify these guiding values at the outset of an evaluation. This process is essential for ensuring that the evaluation is fair, relevant, and addresses what truly matters to those affected by the program. Issues of equity, for example, are highlighted as a key value, emphasizing fairness to all beneficiaries and conformity to standards of natural right, law, and justice without prejudice or favoritism.

Stakeholder engagement is a cornerstone of the CIPP approach, deemed crucial for ensuring the relevance, utility, and ultimate acceptance of evaluation findings.4 Stakeholders are not viewed merely as sources of data but as active participants who can contribute to affirming foundational values, defining evaluation questions, clarifying criteria, providing information, and assessing draft reports. This participatory approach aims to make the evaluation more responsive to the needs and perspectives of those directly involved in or affected by the program.

However, this emphasis on collaboration exists alongside a critical ethical requirement: the evaluator must maintain independence in rendering judgments, writing conclusions, and finalizing reports.14 This creates a delicate balance. While stakeholder input is vital for grounding the evaluation in practical realities and diverse values, the evaluator ultimately bears responsibility for the integrity and objectivity of the findings. Navigating this requires evaluators to possess strong ethical reasoning, facilitation skills, and the ability to transparently manage potential conflicts of interest or undue influence from any particular stakeholder group. Adherence to professional ethical guidelines and standards is therefore essential throughout the CIPP evaluation process.

6. The CIPP Model in the 21st Century and Beyond

As educational landscapes continue to evolve with technological advancements, new pedagogical approaches, and shifting societal demands, the CIPP model’s adaptability and relevance are continually tested and re-examined. Its capacity to provide a comprehensive framework for evaluation remains a significant asset in navigating contemporary educational challenges.

6.1. Adaptability to Emerging Educational Trends (AI, Personalized Learning, Equity Initiatives)

The CIPP model’s fundamental structure has proven remarkably adaptable to emerging educational trends, including the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), the rise of personalized learning environments, and the increasing focus on equity initiatives. The model’s suitability for dynamic real-world projects and its capacity to accommodate uncertainties make it a valuable tool in these evolving contexts. Numerous studies demonstrate its application in evaluating virtual learning environments, online English programs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and inclusive education curricula.

When applied to programs incorporating AI, for instance, the CIPP components can frame critical inquiries: Context evaluation can explore the educational needs AI aims to address and the ethical guidelines governing its use. Input evaluation can assess the algorithms themselves, the data they utilize, and the resources required for equitable access and implementation. Process evaluation can monitor how AI systems are integrated into teaching and learning, and how students and educators interact with them. Product evaluation can then determine the effectiveness of AI in achieving personalized learning outcomes, its impact on student engagement, and any unintended consequences, such as algorithmic bias or data privacy concerns.

Similarly, for equity-focused initiatives, CIPP’s emphasis on assessing beneficiary needs (Context) and evaluating outcomes for all rightful beneficiaries (Product, particularly through its sub-components of Impact and Effectiveness) makes it an inherently suitable framework. The model’s four core questions—What needs to be done? How should it be done? Is it being done? Did it succeed?—provide a “meta-framework” that remains robust even when the specific data points, criteria, and methodologies within each component must be newly defined to address novel interventions. The challenge lies not in the model’s fundamental structure, but in the thoughtful and nuanced application of its components to these new and complex educational realities, ensuring that emerging technologies and pedagogical innovations are evaluated rigorously for both effectiveness and equity.

6.2. Formally Proposed Adaptations and Extensions

The CIPP model has not remained static since its inception; it has been refined by Stufflebeam over the years and has also served as a foundation for various adaptations and extensions by other researchers seeking to tailor it to specific evaluative needs or to integrate its strengths with other frameworks.

One common adaptation involves combining CIPP with Kirkpatrick’s Four-Level Training Evaluation Model (Reaction, Learning, Behavior, Results). This blend is often used for evaluating training programs, where CIPP provides the overarching structure for assessing the program’s context, inputs, and processes, while Kirkpatrick’s levels offer a more granular framework for dissecting the product/outcomes, particularly participant response and behavioral change. For example, the ICT Impact Assessment Model is explicitly described as an extension of a blended CIPP and Kirkpatrick model, with the significant addition of a “challenges” component to specifically address obstacles in technology implementation.107 This addition reflects a recognized need to systematically evaluate factors that hinder the successful integration of ICT in education, a dimension not explicitly central to the original CIPP or Kirkpatrick models alone.

Other conceptual extensions include the incorporation of “confirmatory evaluation” into the CIPP framework. Confirmatory evaluation focuses on the long-term worth and continued relevance of a program, moving beyond initial summative judgments to assess sustained impact and the ongoing validity of the program’s premises. The CIPP model is also seen as compatible with, and can be effectively integrated with, logic models, which visually map the intended relationships between program inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes.

These adaptations and integrations suggest that the core CIPP framework—Context, Input, Process, Product—is widely regarded as a robust and versatile foundation. Rather than being entirely supplanted, it often serves as an anchor to which other specialized tools or conceptual layers are added to enhance its applicability to particular evaluation contexts or to address specific dimensions of program performance in greater detail. The ongoing refinement and combination of CIPP with other approaches underscore its enduring utility and its capacity to evolve in response to the field’s changing needs.

6.3. Future Directions, Unresolved Questions, and the Evolving Landscape of Program Evaluation

The CIPP model is poised to continue playing a significant role in future educational evaluations, particularly as educational systems grapple with increasing complexity, rapid technological change, and persistent equity challenges. However, its continued relevance will depend on its ongoing adaptation and the skill with which it is applied.

A key area for future development lies in articulating more explicit guidelines and potentially specialized sub-frameworks for applying CIPP to emerging domains such as AI-driven educational tools, large-scale personalized learning initiatives, and other advanced educational technologies. While the CIPP structure can frame evaluations of these innovations, specific criteria for assessing elements like algorithmic fairness (Input/Process), data privacy protocols (Input/Process), the ethics of AI use (Context/Product), and the impact on student agency in personalized environments (Product) require further elaboration and consensus within the evaluation community.65 Addressing the ethical implications of these technologies, particularly concerning data privacy and algorithmic bias, will be a critical focus.

Persistent challenges also include ensuring that CIPP evaluations move beyond superficial analysis to achieve genuine depth and insight. This requires highly skilled evaluators who are adept at both the CIPP methodology and the specific subject matter of the program being evaluated. Consequently, evaluation capacity building—developing the skills and knowledge of practitioners to conduct high-quality CIPP evaluations—remains a crucial ongoing need.

Furthermore, unresolved questions persist regarding the optimal balance between CIPP’s inherent managerial and decision-making focus and the increasing demand for more participatory, democratic, and culturally responsive evaluation approaches, particularly in diverse global contexts. While CIPP encourages stakeholder involvement, navigating the complexities of power dynamics, diverse values, and ensuring genuine co-creation in evaluation processes requires ongoing critical reflection and methodological refinement.

The enduring value of the CIPP model in the 21st century and beyond will likely hinge on two factors: its continued conceptual adaptability to new educational paradigms and the capacity of the evaluation community to apply its principles with rigor, nuance, and a commitment to addressing the complex ethical and equity dimensions of modern education.

7. Enduring Value and Strategic Utility of the CIPP Model

The Context, Input, Process, Product (CIPP) model, conceived by Daniel Stufflebeam and colleagues over half a century ago, has demonstrated remarkable resilience and enduring value in the dynamic field of educational evaluation. Its core contributions lie in providing a comprehensive, systematic, decision-focused, and improvement-oriented framework that is applicable to both formative and summative evaluation purposes. The model’s strength is its capacity to dissect complex educational programs and curricula into manageable, yet interconnected, components, allowing for a thorough analysis from initial conception through to ultimate impact.

Throughout this report, the adaptability of the CIPP model has been a recurring theme. It has been successfully applied across diverse educational levels—from K-12 to higher education and vocational training—and in varied contexts, including traditional classroom settings, online and blended learning environments, inclusive education programs, and competency-based initiatives. This versatility stems from its logical structure, which guides evaluators to ask fundamental questions about a program’s rationale, design, implementation, and results.

However, the CIPP model is not without its acknowledged limitations. Its comprehensiveness can translate into complexity and significant resource demands, requiring careful planning and strategic application to be feasible in all contexts. The quality of a CIPP evaluation is also highly dependent on the expertise and diligence of the evaluators to ensure in-depth analysis rather than superficial assessment.

Despite these challenges, the CIPP model remains a cornerstone of program evaluation theory and practice. Its systematic approach and unwavering focus on providing a robust basis for decision-making ensure its continued relevance. When applied thoughtfully, strategically, and with appropriate expertise, CIPP offers a powerful means to not only judge the merit and worth of educational endeavors but, more importantly, to guide their continuous improvement and enhance their positive impact on learners and society. The widespread adoption and adaptation of the CIPP model across diverse fields and geographical locations have solidified its components—Context, Input, Process, and Product—as a foundational lexicon in the language of program evaluation, fostering shared understanding and facilitating collaborative efforts to enhance educational quality worldwide.

[…] experience. However, the distinction can be fluid, and many evaluation models, such as the CIPP model, are applied effectively in both contexts. At its core, curriculum evaluation provides the […]

[…] CIPP Model (Context, Input, Process, Product): A comprehensive framework examining the environment, resources/strategies, implementation, and outcomes to guide improvement. […]