Introduction: Defining Naturalism

Naturalism, as a distinct philosophy of education, posits that nature constitutes the ultimate reality and serves as the primary source for understanding the world and deriving educational principles. It fundamentally asserts that education should align with the natural laws that govern the universe and human development. This philosophical stance generally eschews supernatural explanations and spiritual interpretations, focusing instead on the material and physical world as the sole basis of reality. As articulated in one comprehensive overview, “Naturalism in education is a philosophy where nature is considered the ultimate reality and the source of all philosophical answers. It rejects supernatural powers, sentimentalism, and spiritualism, focusing instead on the material world as the true reality”. This foundational definition immediately distinguishes naturalism from philosophies such as idealism, which prioritize the spiritual or ideational. Furthermore, naturalism advocates for an educational approach that is not primarily dependent on traditional scholastic institutions and literary canons in the conventional sense, but rather on the “actual life of the education”.

The core premise of naturalism is that all phenomena, encompassing human existence and the processes of learning, are governed by immutable natural laws. Consequently, education should be a process of allowing and facilitating the child’s development in accordance with these inherent natural principles. This central idea is often encapsulated in exhortations such as “Return to Nature” and “Follow nature”, indicating a desire to move away from what naturalists perceive as the artificial or corrupting influences of established societal structures and educational formalisms.

The historical emergence and development of naturalism in education can often be understood as a reaction against the perceived artificiality, formalism, and overemphasis on abstract or spiritual elements prevalent in other educational philosophies, most notably idealism. Naturalism’s insistence on nature, the material world, and sensory experience as the bedrock of knowledge stands in direct opposition to idealism’s emphasis on ideas, spirit, and moral or spiritual development. This philosophical counterposition, particularly the subordination of mind to matter, and its call to “break the chains of society”, suggest that naturalism arose as a corrective movement. It sought to ground education in a tangible, observable reality, moving away from paradigms that its proponents found restrictive or misaligned with the authentic nature of human beings.

However, while the emphasis on nature provides a seemingly tangible and experiential basis for education, the very definition and interpretation of “nature” can be ambiguous, leading to practical and philosophical challenges. The core assertion is “nature as everything”, and influential figures like Rousseau advocated for development “according to nature”. Yet, “nature” itself is a multifaceted concept. It can refer to the physical environment, innate human tendencies—which, according to some interpretations, might include aggressive impulses as implied by concepts like “survival of the fittest” —or an idealized state of primordial purity. If the understanding of nature incorporates the principle of “survival of the fittest,” as seen in some interpretations of Spencerian thought, this carries potentially harsh social implications when translated directly into educational practice. The absence of a universally agreed-upon, unambiguous definition of “nature” within an educational context can render the practical application of naturalistic principles inconsistent or susceptible to conflicting interpretations. This inherent ambiguity represents a potential limitation, as hinted at in criticisms regarding its “limited approach” to human development.

Philosophical Concepts of Naturalism

The philosophical framework of naturalism rests upon distinct metaphysical, epistemological, and axiological tenets that collectively shape its approach to education.

Metaphysical Underpinnings (Nature as Reality):

Naturalism fundamentally asserts that nature alone constitutes the entirety of reality; nothing exists beyond the natural world, nor is anything supernatural. The material world is posited as the real world, governed by unchangeable natural laws. This philosophy is frequently characterized as “materialism” , a viewpoint that subordinates mind to matter. A succinct articulation of this stance is that “Naturalism asserts that nature alone is the ultimate reality, and everything originates from and returns to nature. It considers the material world as the real world… Naturalists do not believe in God, Soul, or Divine spirit”. From this perspective, the universe is often conceptualized as a vast, intricate machine, and human beings are considered integral components of this mechanistic order. Such a mechanistic view carries profound implications for understanding human agency, purpose, and the nature of consciousness itself.

Epistemological Stance (Knowledge through Senses and Experience):

In naturalistic epistemology, knowledge is primarily acquired through the senses, which are regarded as the “gateway of knowledge”. Direct experience with nature, tangible objects, and interpersonal interactions forms the core of the learning process. Consequently, naturalism often expresses strong opposition to purely bookish knowledge and verbalism, especially when such learning is detached from direct, lived experience. Rabindranath Tagore, for instance, highlighted the view that “bookish education is not effective for all round development of a learner”. The scientific method, with its emphasis on observation and empirical verification, is considered a key instrument for understanding reality.

Axiological Framework (Values Derived from Nature):

Within the naturalistic framework, values are not perceived as absolute, external, or divinely ordained. Instead, they are considered to be inherent in nature and are discovered or realized by living in harmony with its processes. The guiding principle for discerning and adopting values is encapsulated in the maxim, “To follow nature”. Concepts of goodness and badness, right and wrong, are not learned through abstract moral codes but through experiencing the natural consequences of one’s actions. This implies a somewhat relativistic view of values, as they are intrinsically tied to natural processes and individual experiences rather than to fixed, transcendent ideals.

The metaphysical assertion of a universe governed by unchangeable natural laws, with human beings as part of a “huge machine” , strongly suggests a deterministic worldview. This deterministic undercurrent creates a palpable tension with certain educational aims espoused by naturalists, such as “self-expression” and the “fullest development” of the child , which inherently imply a degree of agency and the possibility of transcending predetermined paths. If human development and behavior are largely dictated by these natural laws, as implied by biological and environmental determinism found in some naturalistic thought , the extent to which genuine “self-expression” or “fullest development”—implying choice and unique individual trajectories—is truly possible becomes a critical question. This highlights a potential philosophical inconsistency or, at minimum, a need for a more nuanced interpretation of “development” within a framework that leans towards determinism. Does “development” in this context mean merely the unfolding of a pre-set pattern, or is there latitude for emergent properties and individual deviation from a norm?

Conversely, the epistemological stance of naturalism, with its profound emphasis on sensory experience, learning by doing, and direct interaction with the environment , can be seen as having paved the way for subsequent experiential education movements. The prioritization of “senses as the gateway of knowledge” and “direct experience” , coupled with advocacy for methods like “learning by doing,” “observation,” and the “play way method” , directly prefigures and supports later educational philosophies such as progressivism. John Dewey, a pivotal figure in progressivism, is noted by some sources as a proponent of naturalism , and progressivism itself emphasizes the “whole child” and “active learning rooted in the learner’s experiences. Similarly, Maria Montessori, whose pedagogical methods heavily rely on sensory exploration and self-directed activity within a carefully prepared environment, is also linked to naturalism. Thus, naturalism’s epistemological shift from abstract, text-based learning to concrete, experiential engagement provided a crucial philosophical foundation for these influential modern educational approaches. Its impact is not merely historical but foundational to many contemporary child-centered practices.

Naturalistic Education: Key Proponents and Their Philosophies

Several influential thinkers have shaped and propagated the principles of naturalism in education, each contributing a unique perspective rooted in their broader philosophical outlooks and cultural contexts.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778): Education in Accordance with Nature’s Plan

Often hailed as the “father of naturalism” in education , Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s seminal work, Emile, or On Education, stands as a cornerstone text for this philosophical approach. Rousseau’s educational philosophy is built upon several core ideas. He posited the inherent goodness of the child, believing that children are born good and that it is society that corrupts them; therefore, education should aim to protect this innate goodness. Central to his early educational strategy is the concept of negative education, particularly in the early years. This approach suggests that education should focus on shielding the child from vice and error, rather than on the direct instruction of virtues or factual knowledge, allowing the mind to remain undisturbed until its faculties naturally develop.

Rousseau strongly advocated for following nature’s stages, asserting that education must align with the natural phases of child development: infancy, childhood, early adolescence, adolescence, and youth. His work provides a detailed exposition of these stages and the corresponding educational approaches suitable for each. He emphasized learning through experience and the senses, particularly in the early stages, prioritizing direct engagement with the world and learning from the natural consequences of actions over reliance on books or verbal instruction. Furthermore, Rousseau called for respecting the child’s nature and interests, cultivating their innate curiosities, and allowing them the freedom to be children. The ultimate goal of Rousseau’s educational model was to cultivate a “natural person”—an individual who is self-reliant, capable of adapting to society, and guided by reason developed through authentic, natural experiences.

Herbert Spencer (1820-1903): Naturalism, Science, and Social Darwinism in Education

Herbert Spencer was a highly influential figure for his application of scientific principles and evolutionary theory to the field of education. His widely read essays on the subject were collected in the volume Education: Intellectual, Moral, and Physical. Spencer’s core educational idea was that the primary aim of education is to prepare individuals for “complete living. To achieve this, he proposed a curriculum based on life activities, classifying human activities in order of their importance for survival and well-being: ) activities for self-preservation; ) activities for securing the necessities of life (vocations); ) activities for the upbringing of children; ) activities for maintaining social and political relations; and ) activities for the enjoyment of leisure. He argued that the curriculum should reflect this hierarchy, prioritizing knowledge and skills most conducive to these aspects of life. This systematic approach represented a significant contribution to curriculum theory.

Spencer was a fervent champion of science in the curriculum, believing scientific subjects to be far more valuable for modern life than traditional literary ones. He also stressed the importance of self-development, observation, problem-solving, physical exercise, and discipline derived from experiencing the natural consequences of one’s actions rather than from imposed punishments. A more controversial aspect of Spencer’s philosophy was his embrace of Social Darwinism, the assertion that the principles of evolution, including “survival of the fittest,” apply to human societies and individuals. This element of his thought has been widely criticized for its potential to justify social inequalities and neglect the needs of the less privileged.

Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941): A Naturalistic Vision in the Indian Context

The Nobel laureate Rabindranath Tagore advocated for an education deeply rooted in natural surroundings, believing that “man’s ultimate happiness lies in the lap of nature”. His educational philosophy emphasized harmony with nature, viewing interaction with the natural world as essential for learning and for the healthy development of both body and soul. This conviction led him to establish Santiniketan, later Visva-Bharati University, as a center of learning situated in a serene natural environment, aiming to foster a holistic educational experience.

Tagore was a strong proponent of freedom and creative self-expression for children, condemning what he saw as the excessive intellectualism of conventional education. He was deeply critical of bookish, confined education, famously likening formal institutions to a “Cage” and students to “bondage parrots” in his essay “Sikshar Herpher”. He believed that true learning should occur through active engagement with the environment, even extending to activities like walking, climbing, and performing daily tasks, rather than being confined to the four walls of a classroom.

Brief Overview of Other Influential Figures:

While Rousseau, Spencer, and Tagore are central figures, other thinkers have contributed to or share affinities with naturalistic educational thought.

- Francis Bacon (151-12): Though not primarily an educational theorist, Bacon’s emphasis on inductive reasoning and empirical observation, which laid groundwork for the scientific method, aligns closely with naturalism’s epistemological preference for knowledge derived from sensory experience and systematic investigation.

- John Dewey (1859-1952): More commonly associated with pragmatism, Dewey’s philosophy also contains strong naturalistic elements. His emphasis on experience as the medium of learning, the importance of the child’s interests as a starting point for education, and his view of education as growth resonate with naturalistic principles. Indeed, Dewey is described as a thinker emerging from the confluence of “naturalism and pragmatism,” who rejected immaterial entities in explanations and viewed education as a set of activities directed towards the enlargement of the student’s knowledge.

- Maria Montessori (1870-1952): The Montessori method, with its emphasis on child-centered learning, self-directed activity, and sensory exploration within a meticulously prepared environment, shares significant common ground with naturalistic ideals of respecting the child’s developmental pace and facilitating learning through direct experience.

- Maria Montessori (1870-1952): The Montessori method

An examination of these proponents reveals that while all champion “nature” as central to education, their specific interpretations and applications of this concept diverge, reflecting their unique cultural contexts and philosophical emphases. Rousseau’s “nature” often signifies an idealized state of inherent human goodness, a benchmark against which societal corruption is measured, leading to his prescription of “negative education” to protect this innate purity. Spencer’s conception of “nature” is heavily informed by 19th-century evolutionary biology and scientific laws, resulting in a curriculum meticulously structured for “survival” and “complete living,” based on observable human activities. His “nature” unflinchingly includes the competitive dynamic of “survival of the fittest.” In contrast, Tagore’s vision of “nature” is a profound source of aesthetic, spiritual, and holistic development, emphasizing harmony and creative expression within natural surroundings, a perspective deeply imbued with Indian philosophical traditions. These variations demonstrate that “following nature” is not a monolithic directive within naturalism. It can yield quite different educational prescriptions depending on whether “nature” is primarily perceived as a benign guide, a set of immutable scientific principles, a competitive arena for existence, or a wellspring of spiritual solace and creative inspiration. This diversity enriches the naturalistic tradition but also contributes to its inherent definitional ambiguity.

Furthermore, a paradox emerges concerning freedom and guidance. Naturalist thinkers, particularly Rousseau, are strong advocates for granting maximum freedom to the child, allowing for unfettered natural development. Spencer, too, emphasized self-development and discipline arising from natural consequences rather than external imposition , and Tagore championed freedom for children. Yet, the very act of designing an educational system, even one predicated on “negative education” or “natural consequences,” inevitably implies a degree of adult intervention, structuring, and guidance. Rousseau, for example, meticulously outlines the stages of Emile’s education, with the tutor (an adult figure) carefully, albeit subtly, orchestrating experiences. Spencer designs a specific hierarchy for curriculum content , and Tagore established an institution with a distinct ethos and learning environment. This reveals an intrinsic tension: truly unguided “natural” development is arguably an impossibility within any intentional educational framework. The naturalist educator, even when aiming for maximal freedom, remains an architect of the child’s environment and experiences. The commonly cited role of the “teacher as observer/facilitator” is still an active one, involving conscious choices about what to observe, when to facilitate, and how to structure the learning milieu. This tension between the ideal of absolute freedom and the necessity of some form of guidance is a critical point for evaluating the practical application and philosophical coherence of naturalistic ideals.

The following table provides a comparative overview of the core tenets of these key thinkers:

Table 2: Core Tenets of Key Naturalist Thinkers in Education

| Proponent | Key Work(s) (if cited) | Core Naturalistic Contributions to Education | Distinct Emphasis |

| Jean-Jacques Rousseau | Emile | Innate goodness of child, negative education, education in stages according to nature, learning through experience/senses, respect for child’s nature and interests. | Protection from societal corruption; development of the “natural person.” |

| Herbert Spencer | Education: Intellectual, Moral, and Physical | Education for “complete living,” curriculum based on life activities (hierarchy of utility), emphasis on science, self-development, discipline by natural consequences. | Scientific basis for education; preparation for survival and societal adaptation; controversial link to Social Darwinism. |

| Rabindranath Tagore | “Sikshar Herpher” , Santiniketan | Harmony with nature, freedom for creative self-expression, education in natural surroundings, against purely bookish/confined learning, holistic development. | Aesthetic and spiritual development in nature; cultural synthesis; critique of colonial education. |

| John Dewey | (Linked to naturalism in ) | Education as growth, learning through experience and problem-solving, child’s interests as starting point, rejection of immaterial explanations. | Connection between naturalism and pragmatism; education for democratic society (though this aspect is more characteristically pragmatist). |

| Maria Montessori | (Linked to naturalism in ) | Child-centered learning, self-directed activity, learning through sensory exploration with prepared materials, teacher as guide. | Structured freedom within a prepared environment; scientific observation of child development. |

Aims and Objectives of Naturalistic Education

The aims and objectives of naturalistic education flow directly from its core philosophical tenets, emphasizing the development of the individual in accordance with nature.

Self-Preservation and Development:

A paramount aim within naturalistic education is to equip the child for self-preservation. This includes fostering an understanding of how to maintain personal health and contribute to a healthy environment. Herbert Spencer, notably, positioned activities related to self-preservation at the apex of his hierarchy of essential life activities that education should address. Allied with this is the objective of facilitating the “fullest development of the child”. This implies an educational process that allows the child’s inherent capacities and potentialities to unfold naturally, without undue external imposition or distortion.

Self-Expression and Individuality:

Naturalism places significant emphasis on self-expression, often prioritizing it over notions of self-realization as understood in more idealistic philosophies. The educational environment should be conducive to the emergence and articulation of the child’s unique personality, talents, and perspectives. Fostering individuality is therefore a key objective, which involves respecting each child’s distinctive pace of learning, inherent interests, and preferred modes of engagement.

Adaptation to the Environment and Preparation for Life:

Education, from a naturalistic viewpoint, should help the child adjust to their environment and prepare them for the inevitable struggles of existence. This encompasses equipping them with the skills and knowledge necessary to secure the necessities of life. Spencer’s overarching aim of “complete living” is particularly relevant here, as it involves preparing individuals for a range of life roles, including vocational pursuits, responsible citizenship, and effective family membership. A fundamental goal is to enable the individual to lead a happy and comfortable life within the context of the present, real world, rather than focusing on otherworldly or purely abstract concerns.

Other Aims:

Beyond these primary objectives, naturalistic education also encompasses other aims:

- Redirection of Instincts: Some proponents of naturalism suggest that education should aim for the redirection and sublimation of innate human instincts towards socially useful and constructive ends.

- Enjoyment of Leisure: An important, though sometimes overlooked, aim is to enable individuals to appreciate and utilize their leisure time effectively and meaningfully.

- Cultivating Wonder and Curiosity: Naturalistic education seeks to foster a profound sense of wonder and curiosity about the natural world. It aims to encourage students to develop a deep appreciation and respect for nature, understanding their interconnectedness with it.

Within these aims, a potential conflict can be discerned, particularly when drawing from Spencerian interpretations. The aim of ensuring the “survival of the individual” and equipping the child to “struggle to exist” , especially if framed by the Social Darwinist notion that “the fittest alone should survive” , can appear to be in tension with the broader aim of achieving the “fullest development” for all children. If educational resources and focus are primarily directed towards ensuring that the purportedly “fittest” individuals survive and thrive, questions arise regarding the commitment to the “fullest development” of those perceived as less fit or less capable of succeeding in this competitive struggle. This reveals a significant ethical tension within naturalistic aims, particularly when influenced by Social Darwinism. It prompts critical reflection on issues of equity and the universal right to an education aimed at holistic development versus an educational system that might, implicitly or explicitly, prioritize those deemed best equipped for a competitive existence.

Conversely, the emphasis within naturalism on preparing for the “present in the real life” and fostering “adjustment to the environment” can be seen as an early articulation of modern educational concerns regarding relevance and the practical application of knowledge. This focus contrasts sharply with educational philosophies that might prioritize abstract knowledge acquisition, future spiritual salvation (as in some forms of idealism), or classical learning detached from immediate practical utility. The contemporary educational discourse frequently underscores the need for curricula to be relevant to students’ lives, equipping them with skills pertinent to contemporary challenges and ensuring that learning is connected to real-world contexts. Therefore, naturalism’s focus on the present and on practical adaptation, while rooted in its own distinct philosophical framework, shares a common thread with these modern calls for educational relevance and applicability, demonstrating an enduring aspect of its vision.

The Naturalistic Educational Paradigm: Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Learning Environment

The practical application of naturalism in education is manifested through its distinct approaches to curriculum design, teaching methodologies, the roles of educators and learners, concepts of discipline, and the ideal learning environment.

Curriculum: Child-Centered, Experience-Based, and Nature-Oriented

A hallmark of the naturalistic curriculum is its child-centered nature. Naturalists generally do not advocate for a fixed, predetermined curriculum; instead, they argue that the curriculum must be tailored to the individual learner, grounded in their specific needs, interests, aptitudes, and capacities. This approach prioritizes experiential learning, emphasizing hands-on activities and direct interaction with nature and real-world objects over traditional lecture-based or purely bookish instruction. Indeed, literacy-focused subjects are sometimes considered of little value if they are not intrinsically connected to lived experience.

The content of a naturalistic curriculum is inherently nature-oriented. It typically includes subjects such as nature study, biology, physics, physical culture, games, sports, geography, and potentially history and language, provided these are taught through experiential methods. Herbert Spencer’s classification of human activities—self-preservation, vocation, citizenship, home membership, and leisure—provides a structured framework for determining curriculum content, ensuring its relevance to “complete living”. A core principle is the rejection of artificiality in the curriculum, with a strong preference for authentic engagement with the environment.

Teaching Methodologies: Learning by Doing, Observation, Play-Way, Heuristic Methods

The core principle underpinning naturalistic teaching methodologies is direct experience with nature, tangible things, and people. Several key methods are employed to facilitate this:

- Learning by Doing: Students actively engage in tasks and activities, learning through direct participation and application.

- Observation and Excursion: Learning occurs through careful observation of natural phenomena and through educational trips and explorations of the environment.

- Play-Way Method: Play is recognized as a natural and effective medium for learning, particularly in early childhood.

- Heuristic Method: This approach encourages students to learn through discovery, fostering a spirit of inquiry and problem-solving.

- Learning through Senses: Activities are designed to engage and train the senses, considered the primary channels for acquiring knowledge.

- Experiential Learning: This overarching approach emphasizes learning through direct involvement and reflection on experiences. Methodologies such as the Dalton Plan, Kindergarten, the Montessori Method, and various forms of experimentation are also seen as compatible with naturalistic principles due to their emphasis on student agency and active learning. Rousseau’s concept of negative learning is also significant, wherein the teacher refrains from direct instruction in the early years, allowing the child to learn primarily from natural experiences and consequences. Some interpretations also include “Negative Learning” as a method involving the encouragement of criticism and skepticism.

The Evolving Roles: The Teacher as Facilitator and the Student as Active Explorer

Naturalism redefines the traditional roles of teacher and student.

- Teacher’s Role: The teacher is not an authoritarian figure who dispenses knowledge, but rather a guide, facilitator, observer, or “stage-setter”. Their role is often described as being “behind the scene” , subtly orchestrating the learning environment. The teacher sets the stage for learning, protects the children’s freedom and spontaneity, and guides their natural development. They are tasked with providing a supportive and stimulating environment that allows children to follow their own interests and learn at their own pace. In the context of integrating naturalist intelligence, teachers are responsible for providing opportunities for students to engage with nature, encouraging exploration, and integrating these experiences meaningfully into the curriculum. However, a noted limitation is that naturalism can sometimes assign “very little importance to the teacher” , which may be problematic for ensuring comprehensive learning.

- Student’s Role: The child is unequivocally placed at the center of the educational process. The student is an active explorer, learning primarily through their own experiences, observations, and interactions with the environment. They are encouraged to be curious, to experiment, to discover, and to invent.

Discipline: Freedom and Natural Consequences

Naturalism advocates for considerable freedom for the child, minimizing excessive restraint or imposition. Discipline is not typically achieved through punishment meted out by authority figures. Instead, it is expected to arise from the child experiencing the natural consequences of their own actions. For example, if a child carelessly breaks a windowpane, the natural consequence is experiencing the cold or discomfort, rather than receiving a physical punishment. The ultimate aim is the development of self-discipline through free activity and personal experience.

The Ideal Learning Environment: The School in Nature

The ideal naturalistic learning environment is one that is free, flexible, and devoid of rigidity. It should ideally be situated in the “lap of nature,” far removed from the perceived artificialities and distractions of urban centers. Rabindranath Tagore’s Santiniketan serves as a prime historical example of such an institution. Outdoor activities and exploration are prioritized over confinement in traditional classrooms. There should be no rigid, fixed timetable or the dispensing of “ready dozes of knowledge” ; learning should flow more organically from the child’s interactions with the environment.

While the advocacy for a curriculum based on the child’s nature and interests is a cornerstone of naturalism, its actual implementation relies heavily on the teacher’s capacity to accurately perceive and interpret these elements. The teacher must then skillfully structure experiences that are genuinely developmental rather than merely indulgent or aimless. Although the curriculum is intended to be child-centered and driven by individual needs and aptitudes , and the teacher is positioned as a facilitator and observer , a child’s expressed “interests” can be fleeting, superficial, or even counterproductive to long-term development if left entirely unguided. The educator is thus faced with the critical task of discerning which aspects of a child’s “nature” to nurture and which “interests” possess genuine educational value. This demands significant skill, profound insight, and a deep understanding of child development that extends beyond mere passive observation. If the teacher’s role is minimized to an extreme, as some criticisms suggest , or if their interpretation of “natural” interests is flawed or incomplete, a purely child-led curriculum could lack depth, coherence, or fail to expose the child to essential knowledge and skills towards which they might not naturally gravitate. This highlights a significant practical challenge in achieving a harmonious balance between child agency and overarching educational goals.

Similarly, the principle of “discipline by natural consequences,” while appealing in its theoretical simplicity and alignment with natural processes , encounters practical and ethical limitations. This approach works effectively for learning direct physical cause-and-effect relationships, such as the example of a broken window leading to the experience of cold. However, its applicability becomes questionable in situations where the natural consequence of an action could be dangerous or harmful (e.g., a child running into a busy street). In such instances, adult intervention is clearly necessary, overriding the pure unfolding of natural consequences to ensure safety. Furthermore, for complex moral or social transgressions, such as lying, cheating, or bullying, the “natural” consequences might be too delayed, indirect, or insufficient to facilitate the learning of desired social and moral behaviors. Society often imposes consequences (e.g., social disapproval, legal sanctions) that are not purely “natural” in the physical sense but are crucial for maintaining social order and ethical conduct. Therefore, while “discipline by natural consequences” is a valuable principle for certain types of learning, it cannot realistically serve as the sole method of discipline. It necessitates supplementation by adult guidance, clear explanation of rules and expectations, and at times, socially constructed consequences, particularly for ensuring safety and fostering moral development—areas where naturalism has sometimes been criticized for perceived neglect.

Strengths and Contributions of Naturalism to Education

Naturalism, despite its criticisms, has made profound and lasting contributions to educational theory and practice, many of which remain highly relevant today.

Emphasis on Child Psychology and Development:

Perhaps one of naturalism’s most revolutionary contributions was its insistence on giving the child a central and important place in the educational process. It advocated for treating the child as a child, with unique developmental characteristics, rather than as a miniature adult. This perspective prioritized understanding each child’s unique abilities, capabilities, and interests, marking a significant departure from traditional methods that often neglected the psychological and emotional needs of learners. Its focus on development according to natural stages, as exemplified by Rousseau’s work , aligns with and often predates modern psychological understandings of developmental phases.

Promotion of Activity-Based and Experiential Learning:

Naturalism has been a powerful force in promoting activity-based and experiential learning. It strongly advocates for learning through direct experience, hands-on activities, and play, rather than through rote memorization or the passive reception of information. This approach tends to make learning more engaging, meaningful, and lasting. Naturalism motivates the child to acquire knowledge within a natural environment and actively encourages experimentation, discovery, and invention. It has profoundly impacted teaching methodologies by stressing guiding principles such as sequencing learning “from simple to complex” and “from concrete to abstract.

Advocacy for Freedom and Spontaneity in Learning:

The philosophy champions freedom for the child to explore, learn at their own pace, and develop naturally without undue external restrictions or impositions. It recognizes children as inherently curious and motivated to learn, thereby fostering intrinsic motivation rather than relying on external rewards or punishments.

Nature as an Educational Resource:

Naturalism consistently considers nature to be the best teacher and an ideal learning environment. This perspective has directly led to the development of various forms of nature-based education, such as forest schools and outdoor learning programs.

Holistic Growth:

A significant aim of naturalistic education is the holistic growth and all-round development of the child, encompassing physical, intellectual, emotional, and social dimensions.

Catalyst for Educational Reform:

Historically, naturalism has served as a crucial catalyst for developing a clearer psychological, sociological, and scientific understanding of education. It has consistently opposed artificiality, excessive intellectual pretensions, and authoritarianism in education, advocating instead for an approach rooted in the authentic experiences and developmental realities of the child.

The most profound and lasting contribution of naturalism is arguably its initiation of the paradigm shift towards child-centered education. This shift continues to exert a powerful influence on progressive educational theories and practices across the globe. Prior to the rise of naturalistic thought, many educational systems were predominantly teacher-centric, curriculum-driven, and heavily reliant on the rote learning of classical or religious texts. Naturalism, particularly through the impassioned advocacy of figures like Rousseau, radically reoriented the focus onto the child—their inherent nature, distinct developmental stages, individual interests, and lived experiences. This emphasis on “the child as child” and the imperative to tailor education to their individual characteristics was nothing short of revolutionary for its time. Subsequent major educational movements and influential theorists, including Maria Montessori , John Dewey , and the broader progressive education movement , all built upon this foundational child-centric orientation. Consequently, the modern educational emphasis on differentiated instruction, fostering student agency, implementing inquiry-based learning, and respecting developmental appropriateness can all trace a significant lineage back to the core tenets first forcefully articulated by educational naturalists.

However, it is also observable that many of naturalism’s core strengths, such as its advocacy for freedom and child-centeredness, can transform into weaknesses if they are applied to an extreme without a balancing consideration for necessary structure, legitimate societal needs, or the essential guiding role of the teacher. While freedom for the child is a key strength , and a child-centered curriculum is highly valued , the notion of “uncontrolled freedom” can potentially lead to chaotic learning environments or a failure to acquire essential, non-instinctual knowledge and skills. An overemphasis on the child’s immediate, expressed interests might inadvertently neglect the development of broader societal understanding or foundational skills that are crucial for long-term success and responsible citizenship—a criticism often leveled against extreme interpretations of child-led approaches. Furthermore, the minimization of the teacher’s role , stemming from a desire to avoid undue interference in the child’s natural development, can leave students without necessary guidance, intellectual scaffolding, or exposure to challenging ideas that expand their horizons. Thus, the very principles that make naturalism appealing and revolutionary—its championing of freedom, its focus on the child, and its emphasis on learning from nature—can, if implemented without nuance or a sense of balance, lead directly to some of its most frequently cited criticisms, such as a perceived lack of structure, the neglect of higher human values, and an insufficient role for the teacher. This suggests that the practical success of naturalism often lies in a moderated and thoughtfully integrated application of its principles.

Limitations and Challenges of Naturalism in Education

Despite its significant contributions, naturalism as an educational philosophy is not without its limitations and has faced numerous criticisms. These critiques address its philosophical underpinnings, its practical applicability, and its potential shortcomings in fostering comprehensive human development.

Potential Neglect of Higher Human Values (Moral, Spiritual, Aesthetic):

A recurrent criticism of naturalism is its perceived neglect of, or insufficient attention to, the moral, spiritual, and aesthetic dimensions of human development. Its strong focus on the material world and its general denial or downplaying of the supernatural or transcendent can lead to a de-emphasis on these crucial aspects of human experience. The prioritization of physical development, sometimes at the expense of robust intellectual and moral growth, is a significant concern for many critics.

The Ambiguity of “Nature” and “Natural”:

The central concept of “nature” itself can be inherently vague and open to widely conflicting interpretations. What is truly “natural” for a human being, especially within the context of complex modern societies, is not always clear. If “nature” is interpreted to include raw, instinctual drives or principles like “survival of the fittest,” as suggested by some readings of Spencer , it can lead to ethically problematic educational implications, potentially justifying neglect or inequitable treatment.

Limitations in Structured Knowledge Acquisition and the Role of the Teacher:

Naturalism’s tendency to devalue or neglect books and the accumulated wealth of human knowledge if not directly tied to immediate, sensory experience is another point of criticism. This stance can limit students’ access to cultural heritage, complex abstract concepts, and the vast repository of human understanding that transcends direct personal experience. Furthermore, the philosophy is often criticized for assigning very little importance to the teacher in the educative process. This can underestimate the vital need for expert guidance, systematic instruction, intellectual mentorship, and the transmission of complex knowledge and skills that may not be spontaneously acquired. The notion that children can develop optimally in a “pure environment” free from societal influences is also seen as flawed, as human beings are inherently social creatures shaped by their social and cultural contexts from birth.

Overemphasis on Freedom and Lack of Definite Aims:

While freedom is a cornerstone of naturalistic pedagogy, too much freedom, if not carefully balanced with appropriate guidance and structure, can be detrimental to learning and development. Additionally, naturalism has been criticized for not offering sufficiently definite or clear aims of education. This lack of clearly articulated ultimate goals can make it challenging to design a coherent, purposeful, and comprehensive educational program that meets diverse individual and societal needs.

Philosophical Criticisms of Naturalism Generally:

Broader philosophical naturalism, from which educational naturalism draws, faces several critiques that have implications for its educational application:

- Circularity of Methodology: Philosophical naturalism is critiqued for its tendency to apply the scientific method to validate itself, thereby losing the independent epistemic means by which to critically evaluate that very method. In an educational context, this could lead to an uncritical adoption of supposedly “scientific” approaches without adequate philosophical scrutiny of their underlying assumptions or broader consequences.

- Ontological Shortcomings: It is accused of failing to provide an adequate account of the nature of reality beyond what empirical science can measure or observe. This may lead to an overemphasis on “what is” at the expense of exploring “what could be,” potentially stifling imagination, creativity, and critical engagement with transformative possibilities. An education system rooted in such a view might lack vision or fail to inspire students to challenge existing norms.

- Abrogation of Philosophy’s Role: By placing an overwhelming reliance on the scientific method, naturalism may neglect deeper philosophical inquiry into fundamental questions of values, purpose, and meaning.

- Limited Approach to Human Development: Critics argue that it fails to account for the full complexity of human nature, including creative forces, spiritual capacities, and the potential for self-sacrifice and altruism that transcend purely biological or environmental explanations.

- Some critiques of ethical naturalism point out that it does not adequately allow for cultural differences in values and can be overly simplistic in its approach to complex moral issues.

Specific Criticisms from Proponents’ Ideas:

Even the ideas of key proponents are not without their critics. For instance, Rousseau’s influential educational theories, while groundbreaking, are sometimes seen as possessing a “utopian color” and his rigid staging of education in Emile as somewhat “mechanical and rigid” in its application.

A core limitation of a strictly materialist naturalism lies in its difficulty in adequately accounting for, or assigning significant value to, aspects of human experience that appear to transcend the purely physical or instinctual. These include capacities such as abstract reasoning, higher-order morality, profound aesthetic appreciation, and spiritual longing. Naturalism, with its emphasis on the material world, sensory input, and observable natural laws , and its frequent denial or downplaying of the spiritual or supernatural realms , faces a challenge here. Critics consistently point to its neglect of moral and spiritual development and its perceived failure to account for “creative forces, spiritual powers”. Human experience is rich with art, music, complex ethical dilemmas, philosophical inquiry, and, for many individuals, religious or spiritual beliefs. These phenomena are not easily explained by or reducible to purely biological instincts or physical processes. This “problem of transcendence” refers to the challenge: if reality is solely comprised of nature, and knowledge is acquired only through the senses, how does naturalism explain and foster these uniquely human capacities for abstract thought, altruism, and the persistent pursuit of meaning that extends beyond mere survival or adaptation to the environment? This inherent limitation directly fuels the criticism that a purely naturalistic education might produce individuals who are well-adapted to the physical world but potentially underdeveloped in crucial aspects of their broader humanity.

Furthermore, the Rousseauian ideal of the inherently good child developing optimally in a “pure” natural environment, shielded from the purportedly corrupting influences of society, tends to overlook the fundamental social nature of human beings and the indispensable role of education in facilitating social participation and cultural transmission. Rousseau’s premise that children are born good and are subsequently corrupted by society , leading to his concept of “negative education” designed to shield the child, evokes an idealized “state of nature” for development, somewhat analogous to the “noble savage” concept. However, human beings are inherently social creatures; their development occurs within a complex social and cultural context from the moment of birth. Education, therefore, is not merely about individual unfolding in isolation; it is also, critically, about enculturation—the process of learning societal norms, values, and the accumulated knowledge necessary to function within and contribute to that society. The idea of developing a “natural person” in isolation first, and only then introducing them to the complexities of social life (as depicted in the educational journey of Emile), is largely impractical and disregards the continuous, dynamic interplay between individual development and pervasive social influence. This constitutes a key reason why a pure, unadulterated form of naturalism is difficult to implement in practice and why it is frequently criticized for neglecting the vital social dimensions of education.

Naturalism A Comparative Analysis with Other Educational Philosophies

Understanding naturalism in education is enhanced by comparing its core tenets, aims, and methods with those of other major educational philosophies, such as idealism, pragmatism, and realism. This comparative analysis highlights naturalism’s distinctive features, its points of convergence and divergence, and its unique position within the broader landscape of educational thought.

Naturalism vs. Idealism:

Naturalism and idealism are often presented as fundamentally opposed philosophies of education.

- Core Contrast: Naturalism posits that reality is matter or nature, knowledge is primarily gained through the senses, values are derived from nature, and education should be child-centered and emphasize freedom. In stark contrast, idealism holds that reality is mind or spirit, knowledge is acquired through reason and intuition, values are eternal and absolute (e.g., truth, goodness, beauty), and education, while valuing the student, often emphasizes the teacher’s role as a guide to these higher ideals, with a focus on moral and spiritual development and the transmission of cultural heritage.

- Metaphysics: Naturalism is fundamentally materialistic, asserting that the physical world is the only reality. Idealism is spiritual or ideational, asserting that ideas or the mind constitute ultimate reality.

- Epistemology: Naturalism emphasizes the senses as the primary source of knowledge. Idealism emphasizes the mind, reason, and the contemplation of ideas.

- Aims of Education: Naturalism aims for self-expression, adaptation to the environment, and self-preservation. Idealism aims for self-realization, character development, and spiritual growth.

- Curriculum: A naturalistic curriculum focuses on sciences, nature study, and physical activities. An idealistic curriculum emphasizes humanities, ethics, arts, and philosophy.

- Role of the Teacher: In naturalism, the teacher is a facilitator, observer, and guide, often working “behind the scenes.” In idealism, the teacher is a moral exemplar, an intellectual guide, and a disseminator of established knowledge and cultural values.

- Discipline: Naturalism advocates for discipline through natural consequences and emphasizes freedom. Idealism stresses self-discipline, adherence to ideals, and often a greater degree of teacher authority in guiding moral development.

Naturalism vs. Pragmatism:

Naturalism and pragmatism share some common ground but also exhibit significant differences.

- Similarities: Both philosophies emphasize the importance of experience in learning, value the child’s interests as a starting point for education, and advocate for activity-based learning methodologies. John Dewey, a key figure in pragmatism, had philosophical roots that included naturalistic elements. Both can be seen as reactions against overly abstract, formal, or traditional approaches to education.

- Differences:

- Reality: Naturalism typically views reality as objective nature, governed by fixed laws. Pragmatism, in contrast, sees reality as dynamic, constantly evolving, and shaped by human experience and interaction; it is not a pre-existing given but is constructed through interaction.

- Knowledge: For naturalists, knowledge is gained primarily through sensory observation of a fixed natural world. For pragmatists, knowledge is gained through practical experience, active experimentation, and problem-solving; “truth” is often defined by what works in practice (“instrumentalism”).

- Values: Naturalism derives values from nature itself. Pragmatism views values as relative to their utility in achieving desired ends and often emphasizes social consensus; values are changeable and context-dependent.

- Focus: Naturalism tends to focus on individual development according to the perceived dictates of nature. Pragmatism often has a stronger social focus, aiming for social efficiency, effective problem-solving in a social context, and preparing individuals for participation in a democratic society.

- Freedom: Naturalism, particularly in its Rousseauian form, often advocates for a greater degree of uncontrolled freedom for the child. Pragmatism, while valuing freedom, tends to conceptualize it within a social context, emphasizing social discipline and shared responsibility; freedom is often more restricted or guided by social considerations.

Naturalism vs. Realism:

Naturalism and realism share some common philosophical ground, particularly in their acceptance of an objective world, but they also diverge in important respects.

- Similarities: Both philosophies emphasize the existence of an objective world external to the mind and recognize the importance of scientific inquiry and empirical observation in understanding this world. Both can be seen as reacting against the purely mental or spiritual focus of idealism.

- Differences: These are often subtle, particularly when comparing philosophical naturalism with educational realism, as distinct from literary naturalism.

- Determinism: Literary naturalism, which is an offshoot of broader naturalistic thought, strongly emphasizes determinism—the idea that human actions are determined by biological and environmental forces, leaving individuals devoid of free will. This often leads to a focus on the struggles of lower classes and pessimistic outcomes. Philosophical realism in education, while acknowledging objective realities and laws, may not be as strictly deterministic, typically allowing for rational choice, the development of reason, and human agency.

- Human Nature: Naturalism, especially in its more extreme or literary forms, can view human beings as essentially “animals” or “human beasts” governed by instinct and passion. Educational realism, by contrast, generally views humans as rational beings capable of understanding objective reality through the combined use of their senses and reason. It aims to transmit essential knowledge and cultivate the intellect.

- Emphasis: Naturalism focuses on “nature” as the primary guiding force and often highlights the raw, instinctual aspects of life. Educational realism focuses on understanding the objective world in its entirety, including social realities and organized bodies of knowledge, with the aim of equipping students with practical knowledge and skills for navigating life. Realism might thus advocate for a more structured curriculum composed of established knowledge domains. One source notes that naturalism can be seen as an “exaggerated version of realism,” sometimes becoming a “chronicle of despair,” whereas realism aims for a “faithful representation of life”.

Placing naturalism on a spectrum of affinity with these other philosophies reveals its unique position. It stands in diametrical opposition to Idealism concerning its core metaphysical and axiological assumptions. It shares significant methodological ground with Pragmatism, particularly in its emphasis on experiential learning, but diverges considerably in its conception of ultimate reality and the nature of truth. With Realism, naturalism shares an objective stance towards the world and an appreciation for scientific inquiry, but it can diverge sharply, especially in its more deterministic strands, regarding human agency and the scope of what constitutes “reality” (i.e., “nature” as all-encompassing versus a broader objective world that includes culture and abstract knowledge). This relational context is crucial for understanding naturalism not merely in isolation but as part of the historical dialogue of educational thought, highlighting what it reacted against, what it influenced, and where its unique contributions and limitations lie.

A deeper philosophical issue that lurks within naturalism’s framework is related to the “naturalistic fallacy.” This fallacy, most famously articulated by G.E. Moore in the context of ethics, involves the attempt to derive prescriptive “ought” statements (about what should be) purely from descriptive “is” statements (about what is). Naturalism in education clearly derives its aims, curriculum, and values from observations about “nature”. It observes what is in nature—developmental stages, laws of survival, sensory input—and then prescribes that education ought to follow these natural observations (e.g., education ought to be staged according to development, ought to prepare for survival, ought to be primarily sensory). The philosophical challenge arises because the mere existence of a phenomenon in nature (e.g., aggression, disease, competition) does not logically necessitate that it is good or that it should be promoted or emulated within an educational system. This implies that educational naturalism, to be ethically coherent and defensible, must implicitly or explicitly employ additional value judgments that go beyond merely observing “nature.” It must engage in a process of selecting which aspects of “nature” are deemed desirable to cultivate, a process that involves human choice and values that may themselves lie outside a strictly naturalistic framework. This represents a profound philosophical critique of its axiological foundation.

The following table provides a structured, comparative overview of these educational philosophies:

Table : Comparative Overview of Educational Philosophies

| Feature | Naturalism | Idealism | Pragmatism | Realism |

| Metaphysics | Nature is the ultimate reality; material world; denies the supernatural. | Mind/spirit is ultimate reality; ideas are real. | Reality is dynamic, evolving, created through experience; utility. | Objective world exists independently of mind; observable facts and laws. |

| Epistemology | Knowledge through senses, experience, observation of nature. | Knowledge through reason, intuition, study of ideas/classics. | Knowledge through active experimentation, problem-solving; “learning by doing.” | Knowledge through senses and reason; scientific inquiry; understanding objective reality. |

| Axiology | Values derived from nature; relative; natural consequences. | Values are absolute, eternal (truth, goodness, beauty); spiritual. | Values are relative, situational, based on utility and social consensus. | Values derived from natural law or reason; objective moral principles. |

| Aims of Education | Self-expression, self-preservation, full development, adaptation. | Self-realization, character development, spiritual growth. | Social efficiency, problem-solving, adaptation to changing world. | Transmit essential knowledge, develop intellect, prepare for practical life. |

| Role of Teacher | Facilitator, observer, guide, “behind the scenes.” | Moral exemplar, intellectual guide, disseminator of knowledge. | Facilitator, guide, project director, encourages inquiry. | Authority on subject matter, transmitter of knowledge and culture. |

| Curriculum | Child-centered; nature study, sciences, physical activity, experience. | Subject-centered; humanities, arts, philosophy, classics. | Problem-centered; practical & utilitarian subjects, projects, experiences. | Subject-centered; organized bodies of knowledge (science, math, humanities). |

| Discipline | Freedom, natural consequences, self-discipline. | Self-discipline, adherence to ideals, teacher authority. | Social discipline, self-control through group activities; restricted freedom. | Orderly environment, development of reason and self-control. |

The Resonance of Naturalism in Contemporary Education

The principles of naturalism, though originating in earlier philosophical eras, continue to resonate and find manifestation in various aspects of contemporary educational thought and practice.

Modern Manifestations and Relevance:

- Child-Centered Learning: The foundational emphasis of naturalism on the child’s needs, innate interests, and developmental stages remains a highly influential concept, particularly in early childhood education, progressive education models, and constructivist approaches to learning. These modern pedagogies share naturalism’s commitment to viewing the child as an active agent in their own learning.

- Experiential and Outdoor Education: There has been a significant rise in educational programs that reflect naturalism’s core tenets, such as forest schools, nature-based learning initiatives, experiential education models, and project-based learning methodologies. The concept of “naturalist intelligence,” as discussed in some contemporary sources, and strategies for its integration into schooling, directly echo naturalistic ideals.

- Play-Based Learning: Particularly in the early years of education, the recognition of play as a vital and natural mode of learning and development is a direct legacy of naturalistic thought, which valued the child’s spontaneous activity.

- Holistic Development: The naturalistic focus on the all-round development of the individual—encompassing intellectual, physical, social, and emotional dimensions—aligns closely with contemporary educational views that advocate for educating the “whole child”.

- Environmental Education: Growing global awareness of environmental issues and the climate crisis has lent new relevance and urgency to naturalism’s call for fostering a deep connection with, and profound respect for, the natural world.

- Inquiry-Based Learning: The heuristic method and the emphasis on learning through discovery, championed by naturalists , are clear precursors to modern inquiry-based and discovery learning approaches that encourage students to ask questions, investigate, and construct their own understanding.

Integration with Current Educational Policies and Practices:

Elements of naturalism can be seen in some contemporary educational policies. For instance, India’s National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 shows alignment with naturalistic principles such as the promotion of holistic growth and the integration of experiential learning methodologies. The focus on developing crucial 2st-century skills like observation, critical thinking, and problem-solving through active engagement with the environment is also highly valued in many modern curricula and reflects naturalistic ideals.

However, there are also significant tensions. The prevalent push for standardized testing, accountability measures based on narrow metrics, and content-heavy curricula in many educational systems can directly conflict with naturalism’s emphasis on freedom in learning, individualized pacing, child-led inquiry, and less rigidly structured educational experiences. Rousseau’s early critique of “exam-oriented” education that stifles children’s natural inclinations and creativity remains strikingly relevant in the face of these modern pressures.

Contemporary education appears to have selectively adapted various principles from naturalism. There is a widespread adoption of many methodological aspects of naturalism, such as experiential learning, child-centered approaches, and the value of play, particularly in early childhood education. However, these methods are often integrated into broader educational frameworks that temper or reject some of naturalism’s more extreme philosophical underpinnings. For example, few modern educational systems fully embrace Rousseau’s concept of “negative education” in its entirety, or Spencer’s “survival of the fittest” as an overarching educational aim. The teacher’s role, while often reconceptualized as that of a facilitator, is generally not minimized to the extent that some naturalists proposed; expert guidance, scaffolding of learning, and direct instruction are still widely valued. Curricula continue to include structured knowledge and the use of books, even as efforts are made to render learning more experiential and relevant. Furthermore, moral and character education, often drawing from philosophical sources beyond naturalism, remains a common component of schooling. This suggests that contemporary education has found considerable practical value in naturalism’s pedagogical innovations but has typically integrated them into more eclectic philosophical frameworks that also accommodate societal demands for structured knowledge transmission, explicit moral development, and a more active and directive role for the teacher. Naturalism’s most enduring legacy, therefore, may lie more in its profound contribution to pedagogical practice and its reorientation of focus towards the learner, rather than in a wholesale adoption of its entire philosophical system.

In eras that are increasingly dominated by high-stakes testing, digital saturation, and intense academic pressure, naturalism’s call for simplicity, a deep connection with the natural world, and an unhurried approach to child development serves as a recurring and arguably necessary counterbalance. It advocates for the child’s overall well-being and the cultivation of an intrinsic love of learning. Contemporary educational systems often face pressures from “exam-oriented” structures , the pervasive influence of screen time, and a documented reduction in children’s outdoor play and engagement with nature. Naturalism, with its historical emphasis on “back to nature” , freedom from overly rigid structures, and learning in natural environments , offers a potent antidote. It critiques “bookish knowledge” that is detached from lived experience and champions the cultivation of wonder and curiosity. In this context, naturalistic principles—as manifested in movements like forest schools or in calls for increased time for play and outdoor learning—re-emerge not merely as historical ideas but as highly relevant responses to the perceived excesses or imbalances of current educational trends. Therefore, naturalism’s enduring relevance may lie significantly in its role as a persistent philosophical reminder to prioritize the child’s holistic development, their connection to the physical world, and their intrinsic motivation, especially when educational systems risk becoming overly artificial, stressful, or detached from authentic, lived experience.

The Lasting Impact and Future Trajectory of Naturalism in Education

Naturalism has carved a distinct and influential niche in the history of educational thought. Its core contributions—most notably the radical reorientation towards child-centeredness, the championing of experiential learning, and the profound respect for the natural stages of child development—have irrevocably shaped pedagogical theory and practice. While the unadulterated application of “pure” naturalism is rare in contemporary educational systems, its spirit and many of its foundational principles infuse numerous aspects of modern schooling, particularly in early childhood education, progressive models, and environmental education.

The enduring legacy of naturalism is evident in the widespread acceptance of the child as an active agent in their learning, the value placed on hands-on experience, and the understanding that education must be sensitive to the individual learner’s needs and interests. It has provided a powerful critique of overly formal, abstract, and authoritarian educational methods, paving the way for more humane, engaging, and developmentally appropriate approaches.

However, naturalism also presents ongoing challenges. The ambiguity of “nature” itself, the potential for neglecting higher-order intellectual and moral development if applied too rigidly, and the practical difficulties in balancing its ideals of freedom with the legitimate demands of structured learning in diverse societal contexts remain points of critical discussion. The tension between individual natural development and the needs of society requires careful navigation.

Looking to the future, the trajectory of naturalistic ideas in education will likely involve further adaptation and reinterpretation. The very definition of “nature” and what it means to learn “naturally” is evolving in a world increasingly shaped by urbanization, technology, and complex global challenges such as climate change. The future relevance of naturalism may hinge on its capacity to adapt its core concept of “nature” to encompass these contemporary realities. Traditional naturalism often idealized pristine, rural nature , a context increasingly removed from the lived experience of a majority urban global population. A strict adherence to learning “far from cities” would severely limit naturalism’s applicability. For naturalism to remain a vital educational guide, its proponents must consider how its core principles—experiential learning, observation, child-led inquiry, connection to the environment—can be meaningfully applied in urban settings (e.g., through urban ecology projects, community gardening, park-based learning initiatives) or even in relation to understanding the “nature” of technology and its profound impact on human development and interaction. Failure to evolve this central concept could risk relegating naturalism to a niche philosophy rather than a broadly applicable framework for future education. The critical question becomes: what does “following nature” truly mean in an increasingly human-altered and technologically mediated world?

Despite these challenges, naturalism’s emphasis on direct experience with and profound respect for the natural world offers a particularly powerful pedagogical foundation for fostering deep ecological understanding and a commitment to sustainability. As environmental crises intensify, the need for an education that moves beyond mere factual knowledge about the environment to cultivate an embodied care and sense of stewardship becomes paramount. Naturalistic pedagogies, such as immersive nature experiences, systematic observation of ecosystems, and hands-on conservation activities, are uniquely positioned to cultivate this deeper, more personal connection to the environment far more effectively than purely classroom-based approaches. This embodied understanding and emotional connection are crucial for developing a strong environmental ethic and motivating pro-environmental action. Therefore, naturalism, with its foundational focus on direct experience of the natural world, is uniquely positioned to contribute significantly to the urgent educational task of cultivating ecological literacy and responsible stewardship for generations to come.

In final synthesis, naturalism stands as a vital, albeit complex, philosophical tradition within education. Its historical impact is undeniable, and its core principles continue to offer valuable insights and a critical lens through which to examine and improve contemporary educational practices, urging a perennial return to the learner’s authentic experience and their profound connection with the world around them.

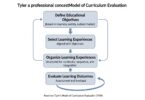

[…] leading indicators and defining what constitutes a valuable “result.” The multifaceted nature of educational outcomes makes the direct, quantifiable linkage often sought in business settings more challenging, […]

[…] impact on student learning in schools, and overall program satisfaction. The comprehensive nature of CIPP aligns well with the rigorous demands of quality assurance and accreditation processes prevalent in […]

[…] and Structure: Its linear, logical, and systematic nature makes it relatively easy to understand and implement. The four-step process provides a clear […]

[…] theory and significant controversy underscores the profound and often challenging implications of behaviorism’s claims about human nature. […]

[…] economy systems are among the most effective applications of operant conditioning in educational settings. These systems involve awarding tokens for specific positive behaviours that the students […]

[…] isolation. This method was groundbreaking at the time but was later criticized for its subjective nature, as different individuals might interpret and report their experiences in varying ways, leading to […]